Can art made by machines ever be real art?

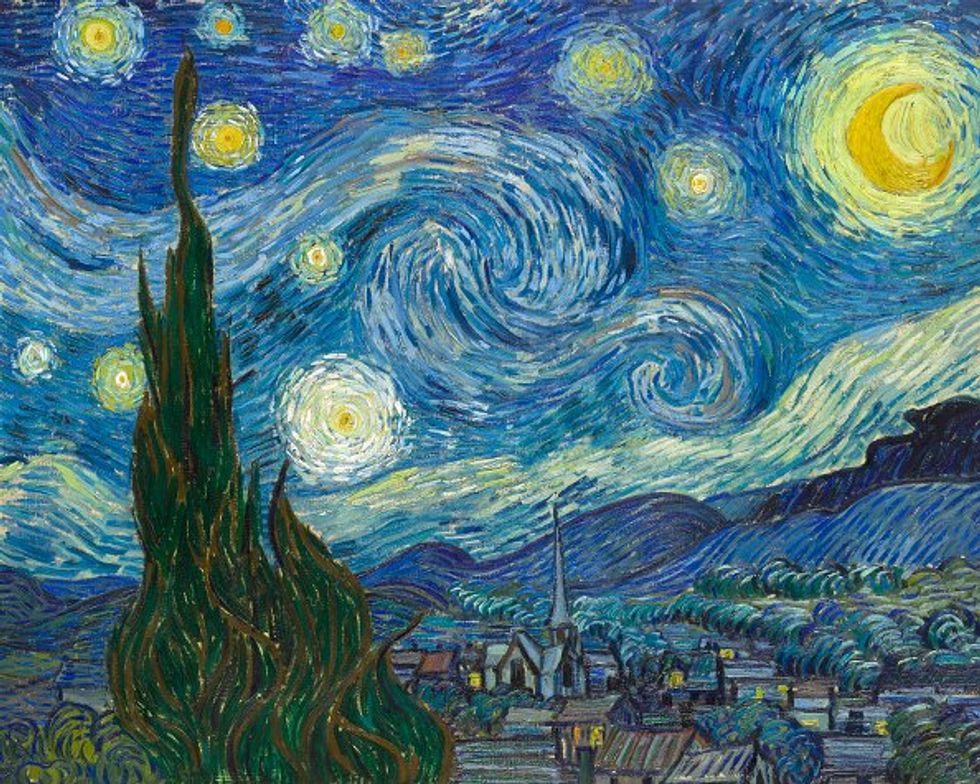

When is a work of art not a work of art? When it’s made by a machine, perhaps? Until recently, this was an all but academic question. Society was not gripped with fear at the prospect of photography destroying the art of painting. Film theorists observed calmly that the motion picture camera was its own agent in the moviemaking process, recording and “noticing” things that no one person involved, even the director or cinematographer, might have picked up at the time of shooting. But because the camera didn’t do its own scripting, acting, editing, color correction, and whatnot, nobody worried that mechanical films would compete with or surpass the normal, human-produced kind. The agonized debate over whether AI art is an oxymoron reveals what, consciously or otherwise, it tries to conceal: a great personal and social agony over the consequences of our individual and collective retreat from making art spiritually, as beings created by God with souls and bodies who must be prepared both for earthly death and, God willing, life eternal. Now, with Hollywood crews historically idle and studios and talent scrambling to survive the streaming revolution, we seem to be in a much different place. The ground truth of the problem — the accelerating substitution of people in arts and entertainment with digital machinery — has trickled all the way up to the New Yorker, which late last month ran a searching, near-viral essay on the topic by sci-fi author Ted Chiang. The thrust of Chiang’s case for “why AI isn’t going to make art” is that each of us is singular — and so our human singularity, when applied to the demands of making the many choices required by artistic undertakings, produces a freshness and novelty unattainable by any machine-induced singularity. “What you create doesn’t have to be utterly unlike every prior piece of art in human history to be valuable,” he concludes. “The fact that you’re the one who is saying it, the fact that it derives from your unique life experience and arrives at a particular moment in the life of whoever is seeing your work, is what makes it new. We are all products of what has come before us, but it’s by living our lives in interaction with others that we bring meaning into the world. That is something that an auto-complete algorithm can never do, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.” Hard to argue! And yet, something about Chiang’s logic is a bit too evasive to hold up under the increasing pressure of the theoretically infinite imagery our gargantuan computers can produce. First, the good stuff: Chiang is right to underscore the centrality of the relationship between artist and audience in defining the meaning and purpose of art. He’s spot-on in insisting that, to take one of his key examples, “the significance of a child’s fan letter — both to the child who writes it and to the athlete who receives it — comes from its being heartfelt rather than from its being eloquent.” And, crucially, he intuits that our ease with language makes us “fall prey to mimicry” by computational models trained on our words at scale — giving in to the diabolical temptation of the so-called “Turing test” to think that superintelligence is defined by the ability to seem superintelligent. It’s some "Princess Bride"-tier foolishness to say a computer is truly smart if it tricks us into thinking it’s truly smart. But today we live under the cultural and spiritual sway of people who really think that it’s better to have the simulation of a thing than to lack the thing itself — an idea that swiftly leads on to believing the simulation is “even better than the real thing,” to quote the old U2 hit, because real is hard, real is costly, real is vulnerable, real is fleeting, real starts fights, real limits us and makes demands, and simulations might not do or be any of those things, or be them a lot less. Just think of the way virtual or artificial sex is presented socially as a great leap forward from the real thing. More and more of our shared human world is being hived off and sold for parts in this fashion, trading away the real for the virtual, simulated, or out-and-out fake. The virtual has become the height of virtue. Chiang’s defense of human art falters in the face of virtualization, collapsing back on a kind of solipsistic sentimentalism. He wants to insist that human beings are intrinsically good, but the evidence he musters is slippery, appealing to our sense of sympathy, cuteness, pity, or even our selfish desire to feel meaningful. This is where, in spite of itself, the evasiveness appears.Listen to the directness with which the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky answers the question of art and its justification. “The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good. Touched by a mast

When is a work of art not a work of art? When it’s made by a machine, perhaps?

Until recently, this was an all but academic question. Society was not gripped with fear at the prospect of photography destroying the art of painting. Film theorists observed calmly that the motion picture camera was its own agent in the moviemaking process, recording and “noticing” things that no one person involved, even the director or cinematographer, might have picked up at the time of shooting. But because the camera didn’t do its own scripting, acting, editing, color correction, and whatnot, nobody worried that mechanical films would compete with or surpass the normal, human-produced kind.

The agonized debate over whether AI art is an oxymoron reveals what, consciously or otherwise, it tries to conceal: a great personal and social agony over the consequences of our individual and collective retreat from making art spiritually, as beings created by God with souls and bodies who must be prepared both for earthly death and, God willing, life eternal.

Now, with Hollywood crews historically idle and studios and talent scrambling to survive the streaming revolution, we seem to be in a much different place. The ground truth of the problem — the accelerating substitution of people in arts and entertainment with digital machinery — has trickled all the way up to the New Yorker, which late last month ran a searching, near-viral essay on the topic by sci-fi author Ted Chiang.

The thrust of Chiang’s case for “why AI isn’t going to make art” is that each of us is singular — and so our human singularity, when applied to the demands of making the many choices required by artistic undertakings, produces a freshness and novelty unattainable by any machine-induced singularity.

“What you create doesn’t have to be utterly unlike every prior piece of art in human history to be valuable,” he concludes. “The fact that you’re the one who is saying it, the fact that it derives from your unique life experience and arrives at a particular moment in the life of whoever is seeing your work, is what makes it new. We are all products of what has come before us, but it’s by living our lives in interaction with others that we bring meaning into the world. That is something that an auto-complete algorithm can never do, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.”

Hard to argue! And yet, something about Chiang’s logic is a bit too evasive to hold up under the increasing pressure of the theoretically infinite imagery our gargantuan computers can produce.

First, the good stuff: Chiang is right to underscore the centrality of the relationship between artist and audience in defining the meaning and purpose of art. He’s spot-on in insisting that, to take one of his key examples, “the significance of a child’s fan letter — both to the child who writes it and to the athlete who receives it — comes from its being heartfelt rather than from its being eloquent.”

And, crucially, he intuits that our ease with language makes us “fall prey to mimicry” by computational models trained on our words at scale — giving in to the diabolical temptation of the so-called “Turing test” to think that superintelligence is defined by the ability to seem superintelligent. It’s some "Princess Bride"-tier foolishness to say a computer is truly smart if it tricks us into thinking it’s truly smart.

But today we live under the cultural and spiritual sway of people who really think that it’s better to have the simulation of a thing than to lack the thing itself — an idea that swiftly leads on to believing the simulation is “even better than the real thing,” to quote the old U2 hit, because real is hard, real is costly, real is vulnerable, real is fleeting, real starts fights, real limits us and makes demands, and simulations might not do or be any of those things, or be them a lot less. Just think of the way virtual or artificial sex is presented socially as a great leap forward from the real thing. More and more of our shared human world is being hived off and sold for parts in this fashion, trading away the real for the virtual, simulated, or out-and-out fake. The virtual has become the height of virtue.

Chiang’s defense of human art falters in the face of virtualization, collapsing back on a kind of solipsistic sentimentalism. He wants to insist that human beings are intrinsically good, but the evidence he musters is slippery, appealing to our sense of sympathy, cuteness, pity, or even our selfish desire to feel meaningful. This is where, in spite of itself, the evasiveness appears.

Listen to the directness with which the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky answers the question of art and its justification. “The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good. Touched by a masterpiece, a person begins to hear in himself that same call of truth which prompted the artist to his creative act.” How similar, on the surface, to what Chiang is trying to say. But how much deeper!

And why? Because Tarkovsky understood that even purely human art, with no robots, algorithms, or code involved whatsoever, will still be fruitless — pointless — in the absence of religion. “An artist who has no faith,” he wrote, “is like a painter who was born blind. … Only faith interlocks the system of images” that makes up the “system of life” itself. “The meaning of religious truth is hope.” To Tarkovsky, art is an ordeal of suffering and joy, one through which the artist and the audience co-create the particulars of hope in one another’s lives. Here is where our singularity and unity are to be found, not in the fact that this or that collection of events, to this degree a jumble, to that degree a narrative, unfolded in this or that human life and not any other.

The agonized debate over whether AI art is an oxymoron reveals what, consciously or otherwise, it tries to conceal: a great personal and social agony over the consequences of our individual and collective retreat from making art spiritually, as beings created by God with souls and bodies who must be prepared both for earthly death and, God willing, life eternal. This retreat leaves a heart-shaped hole into which an infinity of artifice and simulation may rush, but which an infinity can never fill. The pressing issue is not whether a machine might one day artfully trick us by simulating a soul but whether we will, today, put our real souls to work, without which real art will forever elude us.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, World Net Daily, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?