‘It Is Well That War Is So Terrible’: The Battle Of Fredericksburg

On December 13, 1862, during the U.S. Civil War, the Union Army suffered its most calamitous and tragic defeat to date at the hands of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia on the frozen fields south of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

After taking over for the paradoxically arrogant yet timid Maj. Gen. George McClellan following the blood-letting at Antietam in September, the new Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was tasked by President Lincoln to vigorously pursue and destroy CSA Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army now encamped in the Shenandoah Valley in that state. Despite harboring doubts about his own abilities as an army commander, the affable and dapper Burnside concocted a plan to dash due south and lay a pontoon bridge over the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg. His aim was to get ahead of Lee’s army farther to the west and race for Richmond, the Southern Confederacy’s capital.

UNITED STATES – CIRCA 1863: Warrenton, Virginia. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside and staff officers (Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

But Burnside’s plan that relied on speed and surprise almost immediately went awry. The pontoon bridges needed to affect the river crossing were delayed by ten days. By the time they arrived and construction began, Lee had marched his army to Fredericksburg. The Rebels took up a nearly impregnable position south of the town on a rise called Marye’s Heights that presented the defenders with a commanding view of the city and open ground before them.

13th December 1862: Union troops attempting to cross the Rappahannock river during the battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

Despite his plan being foiled — his anxious engineers found themselves laying the pontoon bridges under fire from Rebel snipers who occupied the town along the river bank — the unimaginative Burnside pressed forward anyway. Following a bombardment that all but destroyed the little town, Yankee troops marched over the bridges and fought their way through the streets, whereupon many shamelessly looted the abandoned homes and shops until officers could corral them back into their ranks. The Yankees then formed up for the doomed assault against Lee’s lines.

What the Union troops faced was the suicidal prospect of crossing a half-mile of open, sloping ground to assault a solid line of veteran Rebel troops massed behind the protection of both a sunken road and high stone wall backed by artillery lined hub-to-hub along the crest of the hill before them. While watching the lines of Union blue forming up to make their attack, Lee’s First Corps commander on the Marye’s Heights sector of the line, Gen. James Longstreet, asked his young artillerist, Col. E.P. Alexander, if he thought the position was defensible. Alexander assured him: “General, a chicken can’t live in that field when we open up on it!”

A Union Army battery makes final preparations on the day before the Battle of Fredericksburg, on Marye’s Heights, Virginia, USA, December 1862. (Photo by Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

And so began a series of ill-advised charges up the slopes of Marye’s Heights by a Union Army that proved itself to be as brave as any army in any field; but they were doomed nonetheless. The Confederate lines were so concentrated that for every man at the wall shooting down into the slowly approaching Union lines, two stood behind them with loaded and rammed rifles at the ready to hand the marksman one weapon after another, giving the stone wall’s rate of fire the effect of a machine gun — with the same grisly efficiency. As Alexander predicted, whirring, bouncing projectiles fired from his overheating guns tore into the compact blue formations, killing and maiming groups of men with each round. Thousands of Union troops totaling six divisions were fed into the Rebel meat grinder, one brigade at a time.

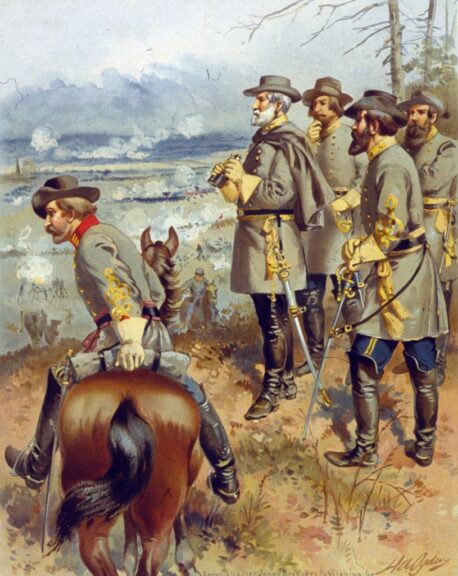

Watching the slaughter from his vantage point above the fighting, Gen. Lee, his stirred warrior blood struggling for equilibrium with his humanitarian nature, offered somberly: “It is well that war is so terrible. We should grow too fond of it.”

7th November 1862: Confederate General Robert E Lee (1807 – 1870) at the battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

After fourteen assaults some 13,300 Union dead and wounded lay strewn in a veritable carpet of blue before the smoke-obscured Confederate lines (to the South’s 4,500, many of whom listed as “missing” had just slipped away to nearby homesteads for Christmas). Although he contemplated continuing the forlorn attack, Burnside was convinced by his corps commanders that any new assaults would be just as fruitless and bloody so he called the battle off. (Burnside actually wanted to lead a final charge himself, so distraught was he over the carnage he’d unnecessarily inflicted on an army he sincerely loved).

The Union attack against 2nd Corps Commander “Stonewall” Jackson’s more exposed lines east of Marye’s Heights situated in lower swampland on Lee’s right did actually make some progress, but this attack too was repulsed.

For two days in the bitter December cold, the shivering Union survivors trapped in the no-man’s land between the heights and the town, hunkered down on the frozen ground. Many shielded themselves from Rebels taking shots at them from behind the stone wall by piling up the bodies of their fallen comrades to act as macabre breastworks. Soldiers would always remember the sound of .566 rounds thudding into the stiff cadavers. At night the eerie lights of a rare Southern aurora borealis flashed overhead in the starry sky, which the Confederates took as a sign that God Himself was celebrating their astounding one-sided victory.

CHECK OUT THE DAILY WIRE HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE

The surviving Union troops eventually withdrew from the corpse-laden field and made it back through the town and across the Rappahannock to safety.

Col. Joshua Chamberlain of the 20th Maine recounted the retreat under the shroud of night. “We had to pick our way over a field strewn with incongruous ruin; men born and broken and cut to pieces in every indescribable way, cannon dismounted, gun carriages smashed or overturned, ammunition chests flung wildly about, horses dead and half-dead still held in harness, accoutrements of every sort scattered as by whirlwinds. It was not good for the nerves, that ghastly march, in the lowering night!”

After one more botched offensive in late January, during which his plans were foiled by a torrential rainstorm rather than Rebel bullets (forever remembered to history as the “Mud March”) Gen. Burnside resigned as army commander. He was replaced by Gen. Joe Hooker — Lincoln’s fifth new commanding general in two years.

When the Confederates re-occupied the shattered and ransacked Virginia town, Lee asked Jackson how they could put an end to this terrible war and all its needless desolation. “Kill them,” Jackson said coldly while surveying the ruins. “Kill them all!”

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a fund manager and author of three books. His articles have appeared on the pages of Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, New York Post, New York Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, The Blaze, Breitbart, Zerohedge and other outlets.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0