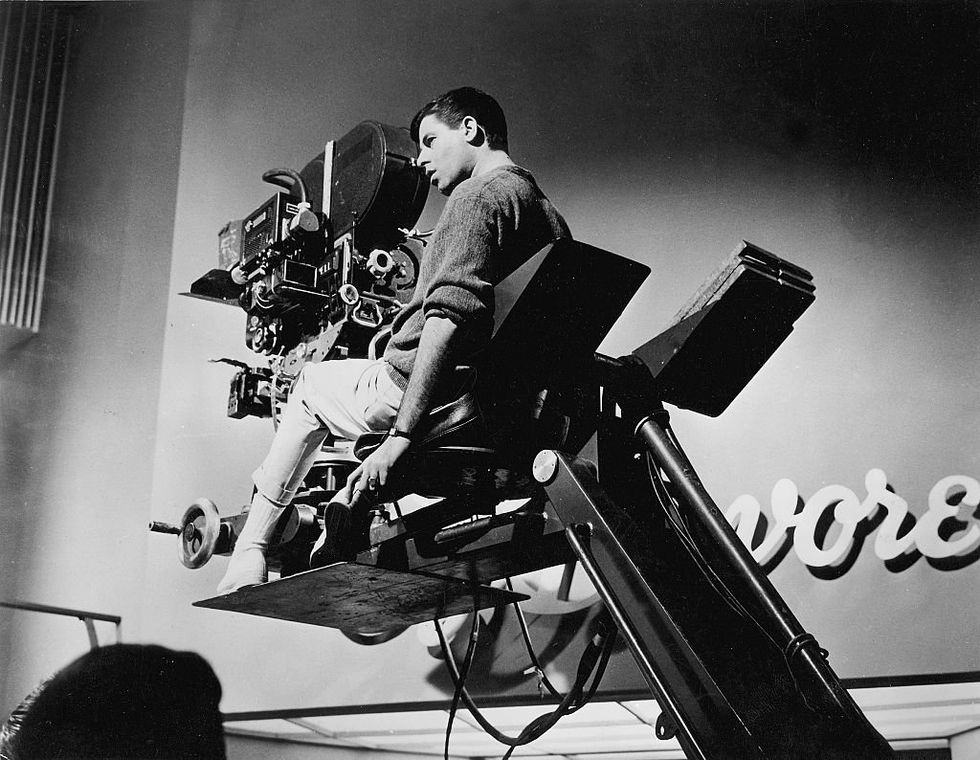

Jerry Lewis: curious, risk-taking craftsman

Very few people have seen Jerry Lewis' “The Day the Clown Cried." This hasn't kept the never-released 1972 film — in which Lewis directs himself as an alcoholic circus clown in Auschwitz who finds redemption entertaining children on their way to the gas chambers — from becoming an inside joke among cineastes and comedy nerds. The sheer, misguided hubris of such an undertaking fits perfectly with our image of late-period Lewis: the maudlin telethon host; the obnoxious, out-of-touch elder statesman; the egocentric self-mythologizer. And yet as critic Richard Brody points out, the Holocaust as we now know it was rarely discussed in the early 1970s. The term itself had yet to come into widespread use. Long before Claude Lanzmann or Steven Spielberg or Roberto Benigni (whose “Life Is Beautiful” won two Academy Awards with a similar premise), Lewis “went where other directors didn't dare to go, taking on the horrific core of modern history and confronting its horrors.” Lewis was always one to take big swings. In 1960 he launched his career as a director by producing, writing, directing, and starring in “The Bellboy,” a plotless tribute to comedies of the silent era that Paramount was nervous would be a flop. Audiences loved it. Lewis continued to push himself as a filmmaker, not only with his unforgettable performances and stunning set pieces, but also with his technical mastery. Insatiably curious, Lewis prided himself on knowing every member of his crew and understanding just what they did. This led to innovation: Lewis developed and was the first to use the now-ubiquitous video assist. Long before he became a legend, Lewis thought of himself as “the total filmmaker.” In his 1971 book of the same name, he is frank that his intense, all-in approach comes at a cost. It is often torture when you have complete personal control. … Eventually, you may beg not to have autonomy so that the morons can pass judgment. You can lie back and bleed, whimpering safely, "Look what they did to me." Whatever his artistic failures and personal foibles, it is to Lewis' credit that he never succumbed to this temptation.

Very few people have seen Jerry Lewis' “The Day the Clown Cried."

This hasn't kept the never-released 1972 film — in which Lewis directs himself as an alcoholic circus clown in Auschwitz who finds redemption entertaining children on their way to the gas chambers — from becoming an inside joke among cineastes and comedy nerds. The sheer, misguided hubris of such an undertaking fits perfectly with our image of late-period Lewis: the maudlin telethon host; the obnoxious, out-of-touch elder statesman; the egocentric self-mythologizer.

And yet as critic Richard Brody points out, the Holocaust as we now know it was rarely discussed in the early 1970s. The term itself had yet to come into widespread use. Long before Claude Lanzmann or Steven Spielberg or Roberto Benigni (whose “Life Is Beautiful” won two Academy Awards with a similar premise), Lewis “went where other directors didn't dare to go, taking on the horrific core of modern history and confronting its horrors.”

Lewis was always one to take big swings. In 1960 he launched his career as a director by producing, writing, directing, and starring in “The Bellboy,” a plotless tribute to comedies of the silent era that Paramount was nervous would be a flop. Audiences loved it.

Lewis continued to push himself as a filmmaker, not only with his unforgettable performances and stunning set pieces, but also with his technical mastery. Insatiably curious, Lewis prided himself on knowing every member of his crew and understanding just what they did. This led to innovation: Lewis developed and was the first to use the now-ubiquitous video assist.

Long before he became a legend, Lewis thought of himself as “the total filmmaker.” In his 1971 book of the same name, he is frank that his intense, all-in approach comes at a cost.

It is often torture when you have complete personal control. … Eventually, you may beg not to have autonomy so that the morons can pass judgment. You can lie back and bleed, whimpering safely, "Look what they did to me."

Whatever his artistic failures and personal foibles, it is to Lewis' credit that he never succumbed to this temptation.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, World Net Daily, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?