Saving El Salvador with 'the world's coolest dictator'

On the flight from Newark to San Salvador, I watched Oliver Stone’s 1986 movie “Salvador.” It had made a big impression on me as a Reagan-era high-schooler; now that I was about to land in the country for the first time, I was curious if it still held up.

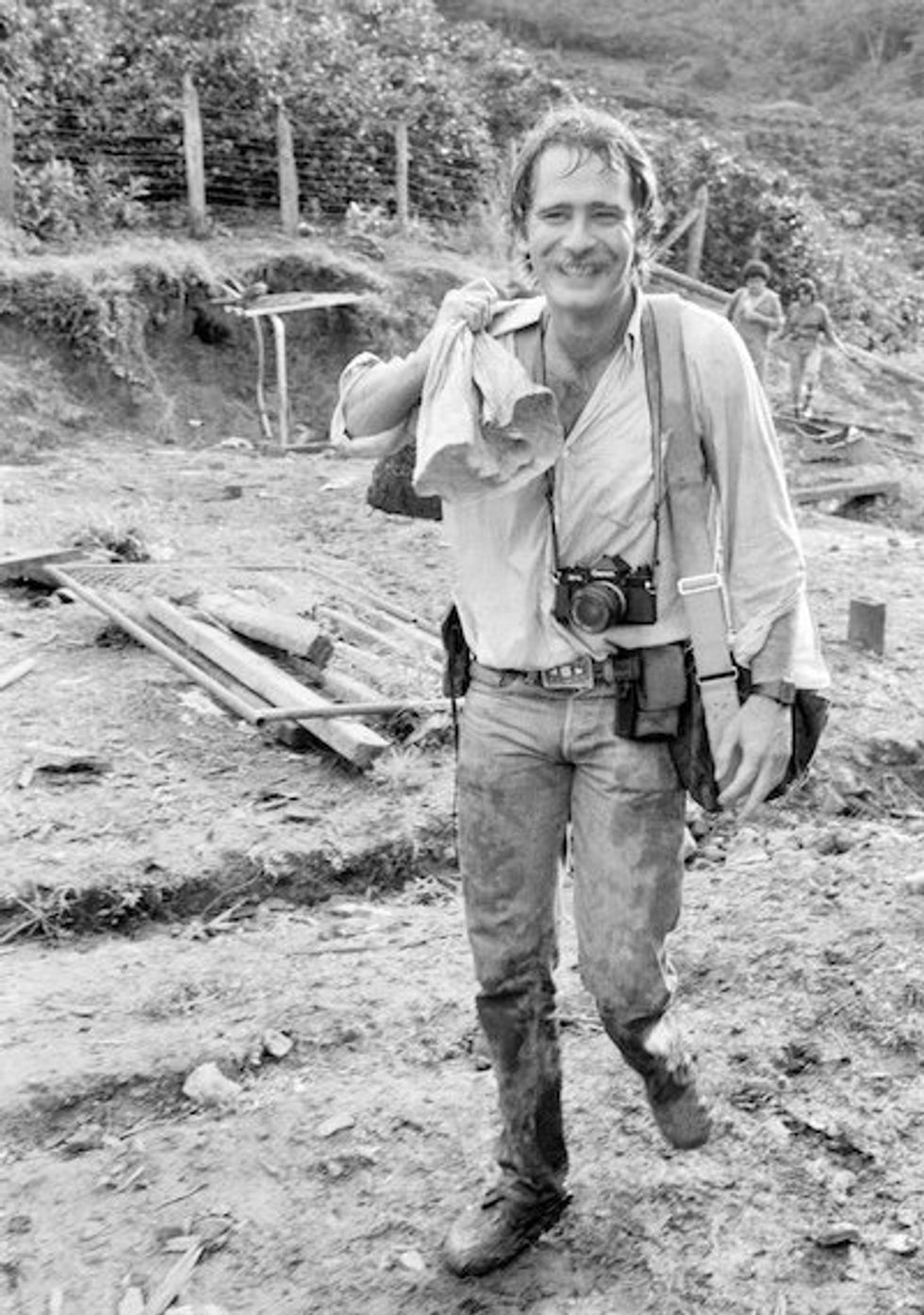

Stone himself didn’t know much about El Salvador the one time he visited in 1985. He went there to scout locations with journalist Richard Boyle, whose exploits covering the still-raging civil war formed the basis for the screenplay he co-wrote with Stone.

Solce’s camera also deftly captures the excitement at the polls. An exuberant man wearing an 'El Salvador' presidential sash compares Bukele to 'the internet.'

Boyle had impressive connections and indefatigable enthusiasm. On his plan to borrow choppers from the Salvadoran air force: “We can pull off an 'Apocalypse Now' helicopter attack … for less than fifty grand!” But these weren’t enough to convince anyone to mount a Hollywood production in an active war zone. So they shot in Mexico instead.

In one gruesome scene, the movie recreates El Playon, the field of lava rock where paramilitary death squads dumped the civilians they murdered.

Boyle (played by James Woods as a fast-talking opportunist) and his old photojournalist buddy Cassady (John Savage) gingerly climb over the bodies of half-clothed men, women, and children as they philosophize about “capturing the nobility of suffering.”

“You gotta get close to get the truth. … You get too close, you die,” Cassady muses.

Claude Urraca/Getty Images

Claude Urraca/Getty Images

First-world problems

I seem to remember this kind of pretentious blather going over better in the 1980s. That was the heyday of the war correspondent as countercultural movie hero. Before “Salvador” there was “The Year of Living Dangerously” (Mel Gibson in 1960s Indonesia), “Under Fire” (Nick Nolte in Nicaragua), and “The Killing Fields” (Sam Waterston in 1970s Cambodia).

Boyle is by far the most dissolute and cynical of these protagonists, but like them he represents a certain ideal: the first-world journalist as courageous yet detached observer, able to plunge into the irrational chaos of third-world conflict and emerge with a credible, objective account of the truth.

How Boyle does this — and what it does to him — is the true subject of “Salvador,” which is why Stone didn’t need to understand the country, let alone film there.

As he said in an interview shortly before the movie’s release, “I didn’t set out to make a message movie about El Salvador. I wanted to do a movie about a correspondent.”

Glory days

On this count Stone succeeded; “Salvador” is a vivid and poignant depiction of an informational ecosystem that has all but collapsed. The American media simply no longer has the authority to present itself as the arbiter of truth — not to Americans and certainly not to citizens of some other country.

Getty Images/Robert Nickelsberg

Getty Images/Robert Nickelsberg

Many journalists (especially those working for prestigious legacy institutions like the New York Times and the Washington Post) are in deep denial about this — even as they describe their own country’s decline into a kind of third-world dystopia at the hands of Donald Trump.

Of course, Trump is to blame for their loss of status, but not in the way that they think. He was the figure who finally forced them to drop their pose of superior neutrality and reveal themselves to be just as politically motivated as any other faction warring for control. “Democracy dies in darkness” is as much a partisan battle cry as Make America Great Again, and everybody knows it.

As the writer and critic Titus Techera points out, the collapse of the old media model offers an opportunity for those able to adapt to new technology. Trump was the first candidate to realize the potential of Twitter to reach voters directly; more recently, he used long-form podcasts to communicate in a more thoughtful, deliberate style than his wildly popular rallies allowed.

This opportunity naturally extends to countries as well as candidates. And at the moment, there’s no better example of a leader harnessing technology to redefine his nation’s place in the international order than El Salvador’s young, charismatic president, Nayib Bukele.

Iron fist

The remarkable transformation Bukele has achieved since taking office in 2019 speaks for itself. The onetime murder capital of the world is now more peaceful than Canada, thanks to the systematic arrest and incarceration of the roughly 75,000 gang members who’d been holding Salvadorans hostage in their own country for decades.

Even San Salvador’s charming Centro Histórico, where I would be attending a series of lectures hosted by the Palestra Society, was until recently a no-go zone — disputed gang territory where severed heads and other body parts were liable to turn up.

In retrospect that explains why the lodgings I’d cleverly booked minutes from the National Theater (where most of the event would be held) offered all the charm and hospitality of a CIA safe house.

It was only after my Uber driver called the number for me that a brusque prison matron of a receptionist unlocked the heavy, unmarked door and unceremoniously led me up a gloomy stairwell to a small kiosk, where she indifferently waited for me to summon the Spanish I needed to state my business.

I decided to heed the organizers’ recommendation and stay at the Hilton after all.

Bukele as strongman ...

Bukele’s crackdown on crime was bound to attract international attention, but the tech-savvy Millennial had the foresight to get ahead of the story.

Like many a startup founder, he and his Nuevas Ideas party “built in public,” posting cinematic videos of hundreds of cowed gang members, stripped to their underwear and herded into prison in perfect formation.

The sweeping arrests and mass trials required a so-called state of exception that suspended civil liberties; instituted in March 2022, it remains in effect to this day.

The Richard Boyles of the world saw a compelling new villain emerging for their stories. Article after article shifted focus from Bukele’s overwhelming popularity within El Salvador to concern over his “authoritarianism.” The moribund Time featured him on the cover with a one-word headline: “Strongman.”

Bukele was ready for this backlash as well. Instead of trying to stonewall reporters or simply ignore them, he met them head-on, playfully embracing his status as “the world’s coolest dictator.” The foreign press could build its narrative, but so could he — and he had a built-in audience of 6.7 million followers on X with whom to share it.

... and Bitcoin bro

Bukele was similarly proactive when it came to attracting investment in the “new” El Salvador. Key to this was the embrace of Bitcoin. In 2021, El Salvador became the first country to adapt the cryptocurrency as legal tender.

This, too, met with criticism, predictably from the same media establishment that had been stoking fears of a dictatorship. But it also had the effect of attracting a different type of foreigner from those one generallly sees flocking to places like El Salvador.

Instead of the usual NGOs and adviser-bureaucrats, this migration was led by Bitcoiners and the Bitcoin-curious. With them came their fellow travelers — ambitious, independent-minded contrarians whose questioning of conventional wisdom tends to read as right-leaning.

Philosopher king

The Palestra Society sits at the center of this scene. Founded in 2023 by a young American software engineer and Bitcoin evangelist who goes by clusk, the Palestra Society brings together curious and driven individuals passionate about art, philosophy, technology, and optimizing health.

These interests were reflected in the variety of speakers featured over the two-day series, which included critic and writer Catherine Sulpizio, sculptor Fen de Villiers, neurosurgeon and bio-hacking pioneer Dr. Jack Kruse (who advised Bukele on drafting El Salvador’s medical freedom legislation), Beck & Stone co-founder Andrew Beck, writer and editor Ben Braddock, and political theorist (and confirmed monarchist) Curtis Yarvin.

Also in attendance was Bukele’s younger brother Yusef, an economic adviser to the president who was instrumental in the country’s adoption of Bitcoin.

While Bukele himself was not present, he loomed large over the proceedings. This was especially apparent on the first night of the conference, when filmmaker Jessica Solce introduced the world premiere of her short documentary “Forging a Country.”

Art over ideology

Unlike many of the other presenters, Solce does not put her political convictions front and center. She is more artist than polemicist; nonetheless, her work exemplifies a quiet resistance to the tactics of mainstream, commercial documentary film.

A former actor and theater director, Solce fell into filmmaking in 2013, after a spur-of-the-moment decision to document a family friend’s art piece — in which viewers were invited to erase a large-scale pencil drawing of an AR-15 with erasers bearing the names of victims of gun violence.

That initial shoot led to Solce’s 2014 film “No Control,” a careful and nuanced depiction of various personalities orbiting the topic of gun control. It’s common to think of this as a “debate,” but Solce doesn’t frame it that way, instead opting for something more open-ended and less conclusive.

This was out of step with mainstream documentary filmmaking, which tends to favor easily digestible narratives catering to a specific viewership (usually the “liberal” one). While Solce’s film was well reviewed, it also proved surprisingly controversial, scandalizing some viewers with its failure to come down on the “correct” side of the issue.

'A Death Athletic'

One of Solce’s subjects in “No Control” was Cody Wilson, a charismatic former University of Texas law student and avowed crypto-anarchist who had recently designed and fired the world’s first 3D-printed handgun, which he dubbed the Liberator.

Solce would spend the next eight years capturing the story of Wilson and Defense Distributed, the open-source software organization he founded to create and distribute schematics for the Liberator and other 3D-printed firearms. The result was her 2023 film, “Death Athletic.”

Wilson is a controversial figure; Solce’s film documents his legal battles with the State Department, as well as his 2018 indictment for having sex with an underage girl.

But like its predecessor, “Death Athletic” refuses to editorialize. The result is powerful and — especially if you go into it with your mind already made up — disorienting.

Solce’s approach makes Nayib Bukele — a figure known to many in the West exclusively through editorializing — a natural subject for the filmmaker.

Surf's up

“Forging a Country” sticks to a narrow time frame: the few days surrounding Bukele’s re-election in February 2023.

From the start, Bukele’s decision to seek a second term was controversial. El Salvador’s constitution prohibits a president from serving two consecutive terms. It was only after the country’s highest court overruled this that Bukele was able to run. Critics pointed out that the court’s judges had been recently appointed by the Nuevas Ideas-controlled legislature after it dismissed the former judges for corruption.

For the most part, those expressing their “concern” were the usual Western politicians (both Biden and Harris weighed in, as did Secretary of State Antony Blinken) and pundits. Salvadorans, on the other hand, seemed to approve, and Bukele won with more than 80% of the votes.

Encode Productions

Encode Productions

“Forging a Country” dares to take these voters seriously, approaching them with curiosity rather than condescension. What if Bukele and his constituents know what they’re doing?

It’s telling that the image with which Solce opens her film is not one of violence, or unrest, or poverty, but of natural beauty: serene drone footage of the sun-dappled Pacific Ocean just off the country’s coast. El Salvador has long been a top surfing destination, something former ad man Bukele has been eager to promote in his country’s new branding as “the land of surf, volcanoes, and coffee.”

From here the film transports us to the far less bucolic exterior of the United Nations building in Manhattan, cutting to clips from Bukele’s September 2022 address to the General Assembly.

Platforming a president

The very first person to speak in “Forging a Country” is the president himself.

“I come from a people who for a long time have seen themselves as less important than others. I come from a people who have never had the courage to make their own decisions. I come from a people whose destiny has always been controlled by others.”

The cure for this national malady is self-determination, and at the end of his speech, Bukele makes it clear that he’s not asking for the approval of the “international community.”

"I came here, to stand on this podium, in a format I no longer believe in, to say something that most likely won’t change the way powerful countries see the rest of us. But maybe it will change the way we developing countries see ourselves."

Solce intersperses Bukele’s speech with clips alluding to both the country’s future (people celebrating Bukele’s second presidential victory almost 18 months later) and its past (a body in a casket, gang members flashing their tattoos).

Like Solce’s two previous films, “Forging a Country” eschews narration or any other device that would give it a sheen of “objectivity.” In a sense, Bukele himself serves as a kind of narrator; we hear his voice throughout, and his speeches bookend the film.

Solce’s willingness to let Bukele speak for himself, and at length, is quietly subversive.

Our self-righteous, often hysterical news media has developed an allergy to “platforming” public figures who have the wrong kind of politics. Predictably enough, this censorship has undermined the media’s credibility.

Now it is precisely those familiar affectations of “objectivity” that signal incoming bulls**t.

Inside the campaign

If Bukele is a classic Latin American strongman, he’s going about it in a thoroughly modern, transparent way.

Unlike the right-wing military leader in “Salvador” (a fictionalized version of nationalist ARENA party co-founder Roberto D'Aubuisson), Bukele doesn’t make the international press chase him. He’s happy to speak with them, when he’s not bypassing them altogether. “Forging a Country” in part serves to document Bukele’s masterful command of 21st-century media.

Solce began “Forging a Country” on a miniscule budget (she describes her status in the business as “massively independent”) and without any official support from El Salvador. When she failed to secure permission to interview Bukele, she went ahead with the movie anyway.

Despite no direct access to Bukele himself, Solce manages to provide a compelling behind-the-scenes account of the campaign.

Yusef Bukele in particular proves to be a thoughtful surrogate for his older brother. Interviewed in and around his home in the hills on the outskirts of the capital, the charmingly disheveled Bukele seems genuinely bemused by the accusations of authoritarianism.

“We’re doing what the people want. We’re not doing anything different. The people elected my brother as the leader, and the leader says ‘we’re going there because that’s where I think we should go.’ And the people say ‘yes, OK, we’ll go there.’”

Encode Productions

Encode Productions

Like Yusef Bukele, Foreign Minister Alexandra Hill Tinoco has the slightly exasperated tone of someone who is pointing out the obvious. The U.S., she tells Solce, “never took the time to understand that this country needed a chance and that this country needed changes … politically, socially, economically.” Instead, it was content to deal with “past administrations that made a business out of irregular migration … because that represented more remittances to our country.”

Solce’s camera deftly captures the excitement at the polls as well: an exuberant man wearing an “El Salvador” presidential sash compares Bukele to “the internet”; a middle-aged woman who left during the civil war proudly recounts returning to vote “for the first time”; Nayib Bukele greets poll workers as he casts his own vote.

'The entire opposition has been pulverized'

Solce also manages to be there for the moment hours later when Bukele and his wife enter the Palacio Nacional and ascend to its balcony to declare victory.

Encode Productions

Encode Productions

As “Forging a Country” portrays it, it's clearly moment of great unity and optimism, with most of the country rallying around one of the most genuinely popular leaders in history. While international coverage acknowledged the scope of Bukele’s win, it was quick to add qualifiers about its legitimacy.

Strangely enough, publications ranging from Reuters and the New York Times to Fox News and the Washington Post all chose to highlight the same quote from Bukele’s speech, imputing a certain unseemly, power-hungry glee to the president: “The entire opposition has been pulverized.”

In context, these insinuations drop away; Bukele simply seems to be reveling in the mandate he’s been given to make good on his promises.

As far as I can tell, few if any outlets bothered to quote Bukele’s remarks at length. “Forging a Country” does, allowing us to take in Bukele’s stirring and eloquent rebuke of elites who take it upon themselves to “protect” voters from themselves.

People who don’t live in our country, people who don’t know El Salvador, who have never spent any time here, not even to make a connection at the airport, they say the Salvadorans are oppressed.They say Salvadorans don’t like the state of exception, that Salvadorans live in fear of the government.

I want to tell the journalists who are here with us tonight, in total freedom and security, here in the safest country in the Western Hemisphere: Don’t take my word for it. I am just a politician. I am just an elected official.

Believe the Salvadorans. Believe what they are telling you. They are telling you here in this public plaza, they told you in all the national and international opinion polls, even the opposition polls.

And if you don’t believe that, they told you today with the elections.

Americans have tended to regard countries like today’s El Salvador with paternal condescension: Look at the adorable developing democracy toddling its way to freedom.

But, freshly emerged from our own fraught and unusual re-election, should we really be so smug?

A night in the park

Midway through “Forging a Country” we find ourselves in a clean, well-lit San Salvador park at night. It’s bustling with people of all ages, walking dogs, riding bikes, playing basketball. It’s only when Solce trains her camera on a few of them that we realize how remarkable this scene truly is.

A cheerful young basketball player marvels at the simple freedom of movement many of us take for granted: “In the morning you can go to the hills, in the afternoon you can be on the beach.” He can even see friends in neighborhoods that were formerly off-limits. “A couple of years ago, impossible. If I visited, I wouldn’t have left.”

For another man, it’s enough to look around and see all the families spending time together in a public space after dark. “Will I go vote? Yes, I’m going to vote,” he says with wry understatement. “I think the decision is quite obvious.”

As Barack Obama once said, “Elections have consequences.” True, but for a certain class of Americans, those consequences have always remained abstract: Your candidate might lose, but you’ll still have food on the table and a safe place for your kids to play.

Such detachment is a luxury more and more of us can no longer afford. Someday soon we’ll have to stop lecturing other countries and put our own lofty standards to the test at home.

Only then, when we’ve done the hard work of getting our own house in order, will we be in any position to judge a statesman like Nayib Bukele.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0