The Battle Of Luzon, Part 3: The Massacre Of Manila

To truly appreciate the tragedy that unfolded in Manila in 1945, one must consider that up until then the city had been nicknamed “The Pearl of the Orient.” Historian James Scott offers: “In the four decades leading up to World War II, Manila developed into a small slice of America in Asia, home not only to thousands of U.S. service members, but employees of companies like General Electric, Del Monte, and B.F. Goodrich. The city boasted a great quality of life, with department stores and social clubs, golf courses and swimming pools, all in a tropical setting, and at a fraction of the cost of living in the United States.”

Then in December 1941, the Japanese came.

Filthy, ragged, half-starved U.S. prisoners were paraded through the streets of Manila after their 1942 surrender. The sight of their more physically imposing former protectors being ignominiously herded along by diminutive Japanese soldiers was disillusioning. “Filipinos stood and watched in an agony of embarrassment,” recalled Manila journalist Nick Joaquin. “These were the God blessed Americans, supposedly invincible. Now here they were: mighty giants being herded rudely by little Jap soldiers. We would never recover from that loss of innocence.”

For the unlucky POWs, however, their three-year nightmare of criminally sadistic captivity was just beginning. 3,700 U.S. civilians were also caught up in the invasion; they would languish in the Santo Tomas Internment Camp, where they desperately ate dogs, cats, pigeons, rats, insects, anything to survive. On the eve of their liberation, the civilian prisoners starved to death at a rate of three to four per day. (MacArthur’s Philippine guerilla network informed him of this, hence his relentless drive to keep moving).

Believing their new Filipino subjects to be an inferior race, the Emperor’s troops had no qualms about looting food supplies and stores, while stealing vital farm equipment which left fields to rot. By the third year of Japanese occupation — with the exception of Japan’s puppet Filipino government officials and collaborators — starvation was rampant, killing some 500 civilians per day. Hordes of beggars roamed the streets; some went so far as to dig up graves to rob jewelry, watches, anything that could be bartered for a fistful of rice. Parents unable to feed their children might abandon or even sell them. (U.S. intelligence reported that by 1944, it cost less to buy a Filipino child than a hog).

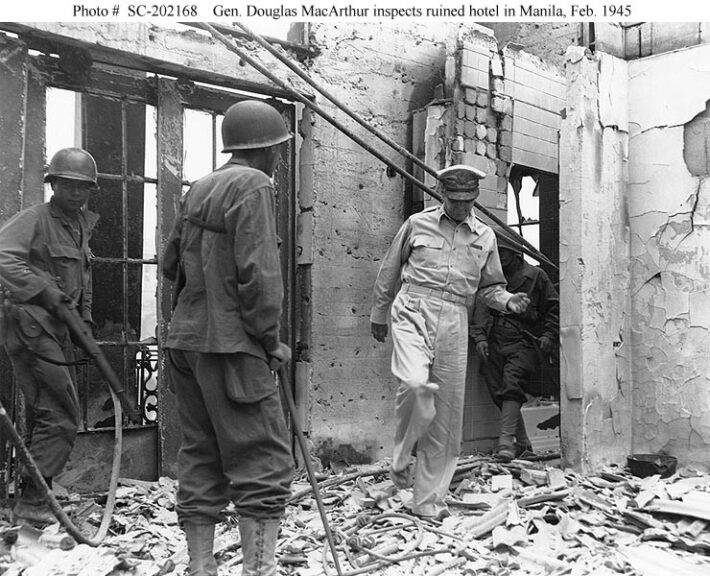

General MacArthur visits the ruins of the Manila hotel that was his pre-war home on Luzon, 23 February 1945. National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

On February 3, 1945, U.S. troops entered the capital. But they did not find an open city. Instead they faced a fortified urban center they would have to take block-by-block, street-by-street, even house-by-house. This came as a rude shock to their five-star commander. Having thoroughly outmaneuvered his enemy, MacArthur expected there to be few if any Japanese left in the area. Other than its sprawling port facilities, which could be demolished before evacuation to deny them to the Americans, the city held no strategic value, as MacArthur himself concluded in 1941 when he abandoned Manila for the more defensible jungle terrain of Bataan, declaring it an open city. Therefore, the notion that Yamashita, a first-rate commander, would choose to defend Manila perplexed him — and then, as the destruction and carnage mounted, infuriate him. But MacArthur’s assumptions had been correct; the Tiger of Malaya had no intention of fighting for the Philippine capital.

Yamashita, however, was dealing with a problem that plagued the Japanese High Command throughout the war. That was the intense rivalry, even downright disdain, between the Imperial Army and Navy top brass. In the case of Manila, while Yamashita pulled most of his army troops out of the city before it was surrounded, some 20,000 Japanese sailors under the command of Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi remained behind to destroy Manila’s harbor.

Although still technically under Yamashita’s command, Iwabuchi and his men didn’t see it that way. They vowed to make a stand, spending the weeks prior to the enemy’s arrival throwing up hasty fortifications, sowing landmines, constructing pillboxes and tank traps. When the Americans approached, the Japanese in the besieged capital opted to get drunk and fight to the death.

And the atrocities began.

Stretcher party brings out a wounded U.S. soldier, following an attack by U.S. troops to liberate Filipino prisoners in the walled city, 23 February 1945. National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

In a mid-February letter to his wife, Gen. Eichelberger wrote with grim understatement, “I hear the big parade has been called off.” In fact, it would have been impossible to march down any Manila street as no thoroughfare would be free of debris and corpses, mostly civilians. By the time the last shot was fired, the Pearl of the Orient would be reduced to a smoldering heap of rubble, whose gutters ran red with the blood of innocents.

It is impossible to adequately describe the horrors the Filipinos endured. Men were bound and shot, bayoneted or mutilated en masse, while patients were strapped to hospital beds before the buildings were set ablaze. Females of every age were brutally gang-raped before being systematically murdered. Babies were tossed in the air and skewered on bayonets by sadistic Japanese who smeared the children’s eyeballs on walls like jelly.

Filipina survivor Carmen Guerrero Nakpil remembered: “It was like a scene from hell. We were running like rats. I saw my classmates dragged through the streets to be raped by the Japanese in the Bayview Hotel. I saw my neighbors cut down by sniper bullets. The killing was terrible.”

20th March 1945: American soldiers watching as refugees pick their way through the debris of North Manila, after safely arriving in the American held part of the city while fighting continues elsewhere. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

When the Japanese burst into the LaSalle chapel, Jose and Juanita Carlos were hiding in the cellar with their children. Jose was dragged off and killed. Then they came back for the rest of the family. Sixteen-year-old Dionisia was bayoneted until unconscious. When she came too she looked for her family. She found her mother and nine-year-old sister and six-year-old brother bayoneted to death, and her nineteen-year-old sister shot dead.

Although it has been claimed that it was a spontaneous eruption of violence against the Filipinos upon whom rogue Imperial troops took out their rage for siding with the Americans (and fear as death closed in), captured Japanese records show that, as with Nanking, the massacre was officially sanctioned, even encouraged. One order went so far as to give explicit instructions on how to commit mass murder: “When Filipinos are to be killed, they must be gathered into one place and disposed of with the consideration that ammunition and manpower must not be used to excess. Because the disposal of dead bodies is a troublesome task, they should be gathered into houses which are scheduled to be burned or demolished. They should also be thrown into the river.”

And yet, throughout the carnage of what has been called the “Pacific Stalingrad”, courageous Filipinos risked their lives braving sniper fire and shell bursts to fill canteens and bring ammunition and food to the Americans hunkered down in the wreckage.

February 1945: A Filipino guerrilla fighting Japanese forces of occupation in Manila. Lacking a tripod for his machine-gun, he has tied the weapon to a fire hydrant. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Despite MacArthur’s repeated calls for the Japanese to surrender, they resisted with suicidal desperation while the American commander anguished over the destruction of the once beautiful city. GIs accustomed to fighting in jungles and beaches had to quickly learn the ways of deadly urban warfare, in which every floor of every building, every stairwell, even closets, were bitterly contested. It was a brutal, often hand-to-hand, form of combat the likes of which had not been seen in the Pacific before, made all the more difficult by the number of civilians.

The Americans, wielding rifles, grenades, satchel charges, flamethrowers, sometimes even rocks and spades, eventually cornered the remaining Japanese in the one-quarter-square-mile fortress of Intramuros, whose walls, twenty-five feet high and forty feet thick, had withstood maritime raiders and earthquakes since the 1570s. General Kenney wanted to bomb the citadel, but MacArthur, aware that many civilians were trapped within, denied his requests, especially the use of napalm. But he did allow the big guns to fire on the holdouts. (In the end, the shelling was so destructive it didn’t really matter.) Eventually the guns breached the walls and the Japanese, including the recalcitrant Iwabuchi, were wiped out or committed ritual suicide.

JOIN THE MOVEMENT IN ’25 WITH 25% OFF DAILYWIRE+ ANNUAL MEMBERSHIPS WITH CODE DW25

With tactics in the capable hands of his field commanders, MacArthur set out to visit the liberated Santo Tomas and Bilibid prison camps. The conditions of the internees horrified him. He was especially moved by the military captives at Bilibid, who made pathetic attempts to stand at attention. In his memoirs he wrote: “Here was all that was left of my men of Bataan and Corregidor…As I passed slowly down the scrawny, suffering column, a murmur accompanied me as each man barely speaking above a whisper, said ‘You’re back,’ or ‘You made it’…I could only reply, ‘I’m a little late, but we finally came.’”

American soldiers who were part of the liberation of the Japanese Bilibid POW camp stop to talk with two internees who had been in the prison camp for two years, Manila, Philippines, February 11, 1945. (Photo by Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

By the time the 29-day fight for Manila was over, and every last Japanese killed, the city had been utterly annihilated with some 11,000 buildings reduced to ruins and ash. 70% of the utilities, 75% of the factories, 80% of the southern residential district and the entire business district had been razed. Of all the Allied cities, only Nanking and Warsaw saw such destruction and civilian carnage. No one will ever know for sure but it is estimated that 100,000 Filipinos died at the hands of the enraged Japanese.

On March 4, 1945, Manila was officially declared secured. The smoking Philippine capital had been liberated, but at a horrific cost to the city and its bewildered inhabitants. CBS News correspondent Bill Dunn would reflect on the tragedy, summing up the horrible effects of war: “The Manila of 1941 was a unique Manila, a Manila that had never existed before, a Manila that would never exist again.”

* * *

RELATED: The Battle Of Luzon, Part 1: Climax Of The Southwest Pacific War

RELATED: The Battle Of Luzon, Part 2: Race To Manila

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages of The Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge, and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0