‘Uncommon Valor Was A Common Virtue’: The Battle Of Iwo Jima

The fall of the Marianas Islands in June 1944 was a devastating blow to the Japanese high command. Not only was it the first battle in which U.S. troops set foot on soil inhabited by Japanese civilians, it provided the U.S. Army Air Force with aerodromes from which they could launch devastating B-29 raids against the home islands. But there was one problem for the Americans. Halfway between the 1,200-mile flight from the Marianas to Japan sat a volcanic island called Iwo Jima. It was well-positioned to not only scramble fighter interceptors from its three airfields to attack the U.S. bombers on their ways to and from their targets, the Japanese could also radio ahead to warn the home islands of the imminent raids. For the USAAF, who also envisioned a forward base for fighter escorts to accompany the B-29s, it was imperative that Iwo Jima be taken. And so the Navy and Marines were called in to do the job.

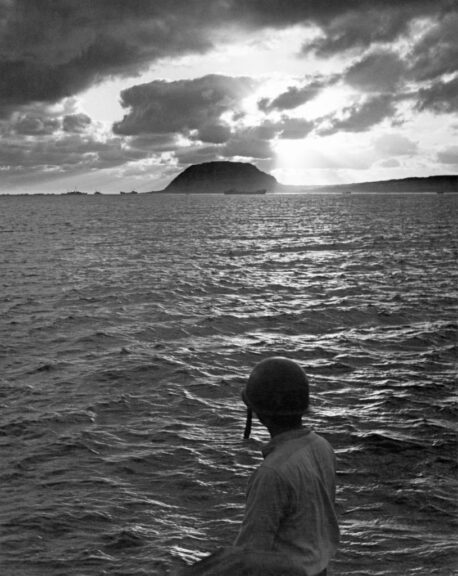

Located 750 miles south of Japan, the five-mile-long Iwo Jima is an isolated porkchop-shaped volcanic island called Iō Tō by the Japanese which literally means “sulfur island.” By the time the U.S. armada of 450 vessels of all types dropped anchor off shore in February 1945, Iwo had been subjected to six months of aerial bombardment. Any vegetation was gone and it presented the Marines waiting to storm the island with a forbidding grayish yellow eight square mile piece of land in the middle of the Pacific. Its only prominent feature was an extinct volcano at its narrow southern tip called Mount Suribachi. It loomed 550 feet over the battlefield and presented an ideal position from which to sweep the entire landing zone with artillery and machine gun fire.

Fritz Olson/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images

The innovative Japanese Gen. Kuribayashi Tadamichi made the most of the nine months from his assumption of overall command of Iwo’s defense to create one of the most formidable tactical positions in the annals of warfare. He knew he could not throw the Americans back into the sea (he told his wife he’d never return). As such, his plan was to inflict as many casualties as possible before the battle was over. Breaking with Japanese military doctrine, and mimicking Gen. Nakagawa Kunio’s brutal defense-in-depth of Peleliu in September 1944, Kuribayashi had his 21,000 troops fortify Iwo with hidden bunkers, gun emplacements, and camouflaged machine gun nests, all interconnected by 11 miles of subterranean tunnels and caves. The island’s defenders, a mixed force anchored around the 106th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army, would not be on Iwo so much as in it. And, as per their gifted commander, they vowed to make the Americans pay dearly for every square foot of ground.

Kuribayashi’s enemy counterpart, Lt. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, the overall Marine commander of the invasion, codenamed Operation Detachment, had asked the Navy for a 10-day preliminary bombardment before commencing the landings. But for several reasons Rear Adm.William H.P. Blandy, who was in charge of the supporting Task Force 52, would only agree to three-day’s worth. Whatever the right course, following the intense naval barrages and air attacks from carriers miles off shore, on February 19 the Marines of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Divisions descended the rope nets into their pitching landing craft and motored for shore.

(Original Caption) 2/25/45-Iwo Jima: Marines of the fifth Marine division ready to land. Getty Images.

It was eerily quiet as the first three waves were deposited onto the forbidding black sands. They met little opposition, prompting some Marines to optimistically conclude the Naval gunfire had wiped out the defenders.

But this was a ruse. Unlike the last major Marine landings on Peleliu — in which the fine 1st Marine Division was bled white — Kuribayashi waited to open fire, allowing the unsuspecting Marines to unload more men and equipment onto the now crowded beach. A beach the Marines would soon discover featured a series of terraces, some as high as twelve feet, consisting of fine volcanic ash which made digging foxholes difficult, “like digging in corn kernels or BBs,” one veteran would remember. The sand also made movement of tracked vehicles off the beach problematic. And it burned to the touch after a while due to the sulfur. Wisps of volcanic smoke rose from the island. It was arguably the most otherworldly battlefield in U.S. history. And it was about to become among the most horrific.

Mondadori via Getty Images

Once satisfied that enough of the enemy had crowded onto the beach like a colony of sea lions, Kuribayashi gave the order to commence firing. Suddenly, as the fourth wave of Marines was making its way ashore, the entire island erupted in the whiz-bang! of exploding artillery shells, the rat-tat-tat of machine guns, and the steady pop-pop of small arms fire. Explosions marched methodically up and down the beach, killing and maiming Marines caught in the pre-sited kill zones that had been rehearsed for months. One veteran, Corporal Ira Hayes, remembered lying prone in a shell hole when another Marine dove in next to him. “Helluva battle!” Hayes shouted. “It’s a f*****g slaughter!” the man yelled back to him above the deafening roar. Hayes then watched in horror as the young trooper jumped out of the hole and ran forward barely ten steps before being decapitated. Such was the chaos and carnage visited upon the Marines from an enemy so well hidden that many veterans would later claim they never saw one alive.

Navy Secretary James Forrestal, hoping to boost sagging public support for the war effort, had accompanied the invasion fleet and given unfettered press access to the combat zone as he’d expected a quick, textbook operation. But it soon became apparent that Iwo Jima was turning into a bloodbath. Within the first 48 hours of the landings over 3,500 Marines were casualties. And it would only get worse over the coming days and then weeks of non-stop fighting.

Injured US marines of the 4th Division at the Battle of Iwo Jima during World War Two, Japan, February 20th 1945. (Photo by US Marine Corps/Getty Images)

By the fourth day of the battle, some 70,000 Marines had made it ashore and were fed into the conflagration and losses were mounting at an alarming rate. But the persistent Americans were making progress. The Marines drove across the southern tip of the island to the far shore, isolating Mount Suribachi. They then doggedly fought their way up the mountain.

On the morning of February 23, D+4, a Marine patrol reached the summit, and a small flag was erected to announce Suribachi was now in friendly hands.

Staff Sergeant Louis R. Lowery, USMC, staff photographer for “Leatherneck” magazine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The men down below craned their necks up to see the Stars and Stripes snapping in the wind on the crest. Wild cheers spontaneously rang out across the island and Navy vessels blared their horns in celebration. Forrestal, on the beach at the foot of the mountain, declared “The raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years!” He ordered a larger flag to replace the original (which he kept as a souvenir, much to the chagrin of the battalion commander whose men took the summit). It was this second, anticlimactic flag raising, which went mostly unnoticed by the combatants, that AP photographer Joe Rosenthal captured in arguably the most famous and inspiring image of the Second World War.

Photo by Joe Rosenthal/Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

But, contrary to popular belief, the seizing of Suribachi was only the beginning of the battle. For an entire month more the fighting would rage. By the time Iwo Jima was finally declared secure on March 26, 1945, practically the entire Japanese garrison (including Kuribayashi whom it is believed committed ritual suicide) would be dead or missing. The cost for the Americans was ghastly: 27,000 total casualties, including 6,100 Marines and some 700 Navy personnel KIA. It was, in fact, the bloodiest battle in Marine history up to that point, and, ominously, the first in the war in which U.S. casualties were higher than those of the island’s defenders.

Iwo Jima presented a grim harbinger of the ferocious Japanese resistance that awaited the Americans with each step closer to their home islands. What kind of hell was in store for them when trying to conquer Japan itself, with its 71 million militarized inhabitants, if this was the butcher’s bill for one tiny speck of land in the middle of the ocean? It was the horrors of Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and then soon after the battle for Okinawa (the bloodiest of the Pacific War) that weighed heavily on President Truman’s mind when he made the decision to drop the atomic bombs to try and put an end to the killing.

As a testament to the dedication of the island’s defenders — as well as an indication of the fanatical defense of the home islands Truman sought to avoid — some 3,000 Japanese refused to surrender. Instead they remained in the subterranean network of tunnels to conduct guerilla-style resistance even as the island was converted into an airbase. The last Japanese soldiers on Iwo Jima surrendered on January 6, 1949 — nearly four years after the start of the battle, and over three-and-a-half years after the war ended!

circa 1945: A US marine cemetery at the foot of Mount Suribachi in Iwo Jima. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Iwo Jima carries a special place in Marine lore. The service’s bravery, determination, and sacrifice prompted Adm. Chester Nimitz to declare of the Corps “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.” But there remains a nagging question. Was the cost worth it? Even as the battle dragged on, USAAF Gen. Curtis LeMay, in command of the Pacific’s strategic bombing campaign, made a monumental decision. High altitude precision bombing had turned out to be ineffective due to the violent effects of the newly discovered 250 mph jet stream at the extreme altitudes in which the new, and expensive, B-29 Superfortress bombers were designed to operate. And so LeMay decided to roll the dice and send the bombers in under the cover of darkness, flying very low-level, and loaded not with conventional explosives but incendiaries to rain fire down upon Japan’s mostly wooden structures.

Dai Nippon was helpless against such nocturnal onslaughts which would lay waste to over sixty cities in the coming months. The fighter protection that Iwo Jima was taken to provide during daylight, high altitude raids in the manner of the European bombing campaigns went largely underused. It has been argued that some 2,000 B-29s with their 10 to 14 personnel each that would have otherwise been lost at sea due to combat damage or mechanical failure landed on Iwo Jima; thus, the saved bomber crews’ lives offset the Marine losses. But this is mere speculation, and seems to be more of an attempt at rationalizing the high cost than anything else. Eighty years later, this remains a subject of debate within military round tables.

Whatever the justification for the landings, Iwo Jima stands among the pantheon of America’s great battles. Few times in history have troops been so tested, faced with such formidable resistance against a skilled and ruthless foe, or such an alien landscape, and come out victorious. The very words Iwo Jima have become synonymous with what the Greatest Generation could achieve when it set its mind to it, and vowed to win no matter the cost.

One wonders if Iwo Jima would have been winnable today. For the sake of our nation, let us hope we are never again placed in a position to answer such a question.

Semper Fi.

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages of The Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge, and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0