Applying Lessons From Ukraine: How to Win in the Indo-Pacific

When Russia launched its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, few expected Ukraine’s underfunded navy to compete with a traditional power. But within months, the naval front reversed and Ukraine transformed its navy into a decisive force in the Black Sea. Throughout the war, Ukraine disabled over one-third of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, sunk its flagship, and provided a glimpse into the future of naval warfare.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

Now, as the U.S. confronts possible war in the Indo-Pacific, these lessons will prove critical. But while Ukraine’s successes—most notably, its imaginative use of maritime drones—are informative, future success requires more than mere replication. Instead, the U.S. must adapt the experiences of Ukraine in the Black Sea to apply them in the Pacific.

Operational Lessons From the Black Sea

Early in the war, Russia’s superior Black Sea fleet destroyed in days what remained of Ukraine’s navy, took control of Snake Island, and severed Ukrainian maritime activity—including critical grain and mineral exports. Employing long range cruise missiles and maneuverable submarines, Russia maintained a steady assault on cities like Odessa and Mykolaiv. For Ukraine, regaining control of the coastline and critical shipping routes seemed unachievable until the sinking of the Black Sea fleet’s flagship Moskva.

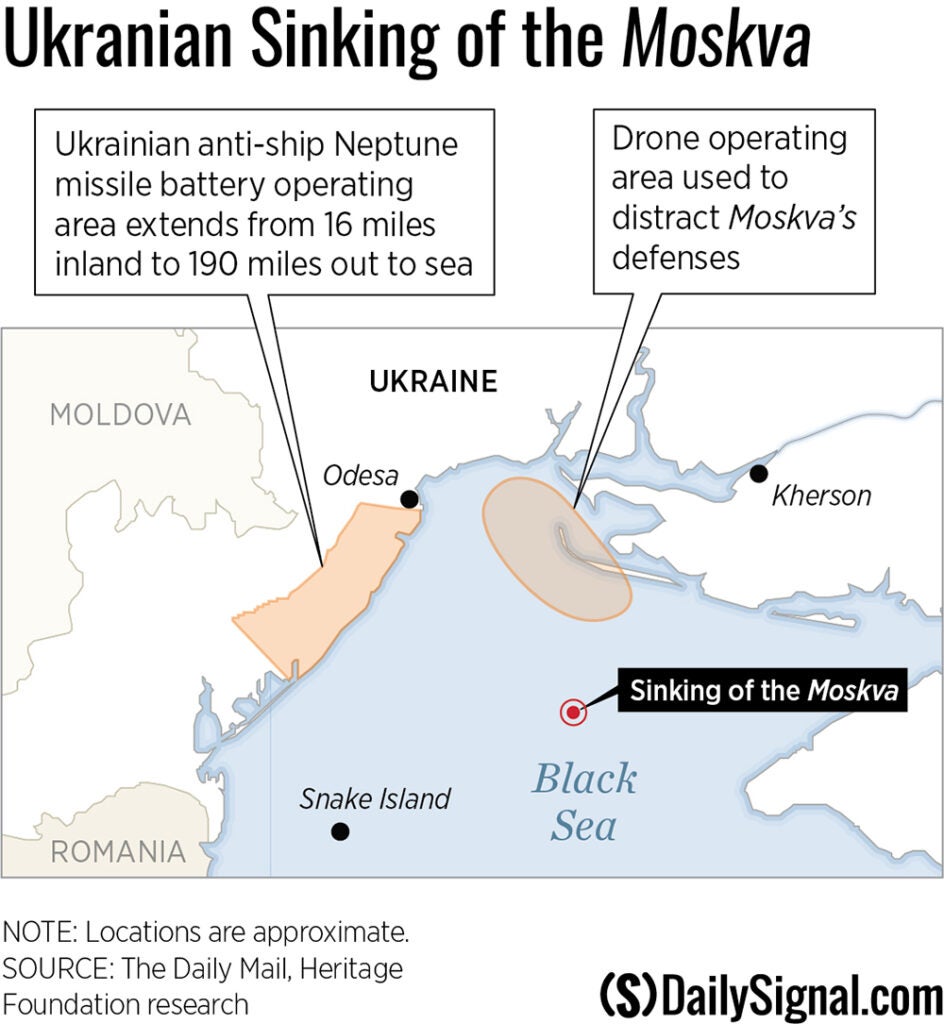

Two months into the war, this effort delivered a much needed, tactically significant morale boost. Ukraine began to retake territory, pushing Russia’s fleet east. Initially, the country used Turkish-built large airborne drones to distract the Moskva’s defenses and sensors, creating an opening for a second attack from long-range land-based cruise missiles. Suddenly, Russia no longer dominated the western Black Sea.

Wartime necessity forced Ukraine to make a pragmatic shift. The country had limited resources and no warships, but it possessed a favorable maritime battlespace for its fledgling drone fleet. Combined with tentative drone success, Ukraine began leveraging imaginative innovation of its asymmetric capabilities.

Success for Ukraine’s drone-based naval offensive required innovative financing and labor approaches. Ukraine combined crowdfunding, state resources, and private talent to fund and accelerate the production of an array of drones at an astounding speed.

At the start of the war, Ukraine depended on Chinese-manufactured drones, with initial domestic building capacity taking months. Now, Ukraine can produce 200,000 drones per month, with turnaround times measured in days.

Tactics evolved quickly and informed near-real-time design changes. Within a few months of the initial invasion, Ukraine had prototypes of maritime drones ready for missions. After that, it wasn’t long before unmanned surface vehicles, the heart of their operations, were produced in serial batches to attack across air, land, and sea.

These systems imposed outsized costs on Russia, with battles forcing Russia into repairs costing up to 235 times the drones’ original cost. In one instance, a combination of Ukrainian drones worth about $2 million damaged the Admiral Grigorovich frigate, likely requiring $450 million to $500 million in repairs.

Technical capabilities partnered with tactical innovation. Ukraine adapted stealth and striker technologies into multi-domain platforms capable of managing multiprong attacks, evolving from uncoordinated strikes to comprehensive night-time drone swarms. In a historic first, this evolution led to a Ukrainian surface drone successfully shooting down a Russian fighter jet with a missile in early May.

Over time, Russian electronic warfare improved, degrading Ukraine’s ability to control drones via traditional radiofrequencies. As a result, Ukraine began employing redundant communication systems to enable agile frequency use to counter hostile signal interference. The country also used satellite systems like Starlink for distant drone surveillance and combat operations. Integrating these capabilities with the broader naval drone campaign proved integral to Ukrainian efforts.

Of course, geography matters. The Black Sea stretches 730 miles east-west, with a length of 160 miles north-south. Ukraine’s long-range Neptune cruise missile can reach around 620 miles, enabling it to cover most of the Black Sea. Meanwhile, Russia’s Kalibr missile has a maximum range of approximately 1,600 miles, covering all of Ukraine from launch sites in the eastern reaches of the Black Sea.

Still, sustained Ukrainian success benefitted partially from a closed water space. Thanks to Turkey closing the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, Russia was unable to replace its losses in the Black Sea.

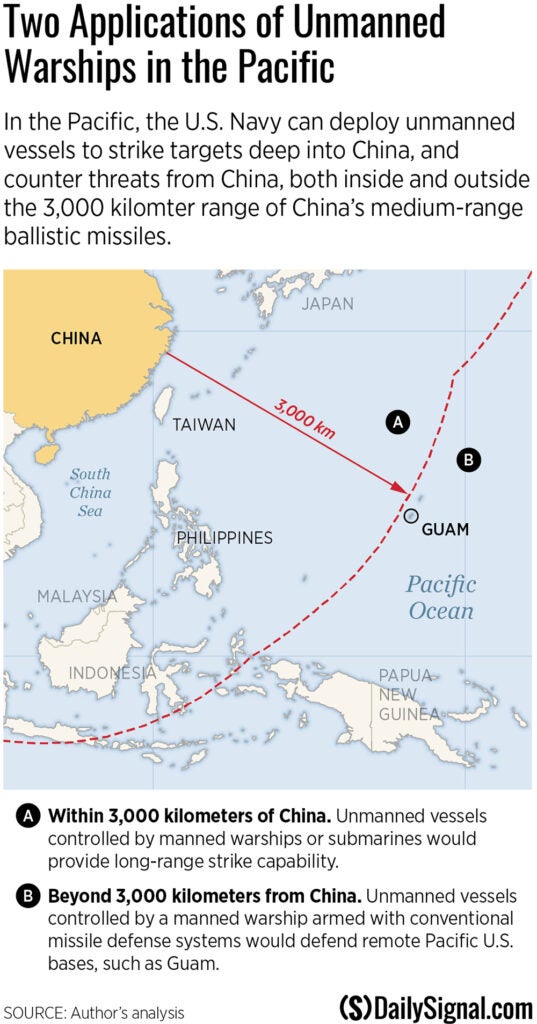

That’s a principle that could be applied in Asia, where the first island chain—if appropriately armed—would pose a military challenge to China. Success would require leveraging geography, basing unmanned platforms and shore-based long range strike weapons in first island chain countries.

Shifting to the Indo-Pacific: A New Theater

War in the Pacific will be defined by both the nature of the threat and geography, with distinct operations emerging in key naval subregions: the East China Sea and Yellow Sea, the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and the Philippine Sea.

The East China Sea and the Yellow Sea

As China pursues control of the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea, U.S. forces will likely struggle to compete without a robust naval force. However, the shallow water depth and relatively constrained maritime space offer an opportunity to employ tactics like Ukraine’s.

Taiwan

A Chinese invasion, once remote, is now increasingly probable. The Taiwan Strait is a shallow-water corridor, just 80 miles at its narrowest—making a rapidly deployable active naval defense critical. Drones will be necessary for detecting and responding to incoming attacks. Rapid placement of blockades can channel Chinese naval forces through chokepoints into kill zones loaded with mines, shore-based missiles, and unmanned vehicles—raising the cost of invasion.

The South China Sea

The South China Sea is at the forefront of strategic competition. Since 2015, China has used an archipelago of manmade island bases to sustain a large naval presence, constraining U.S. peacetime responses. In wartime, this sea will become a critical battleground.

As part of the Task Force Ayungin, the U.S. has worked with the Philippines to push back on China’s excessive maritime claims. These efforts would benefit from building on the lessons from the US Navy’s Task Force 59—a unit formed to integrate unmanned platforms, sensors, and artificial intelligence analytics for maritime domain awareness.

The Philippine Sea

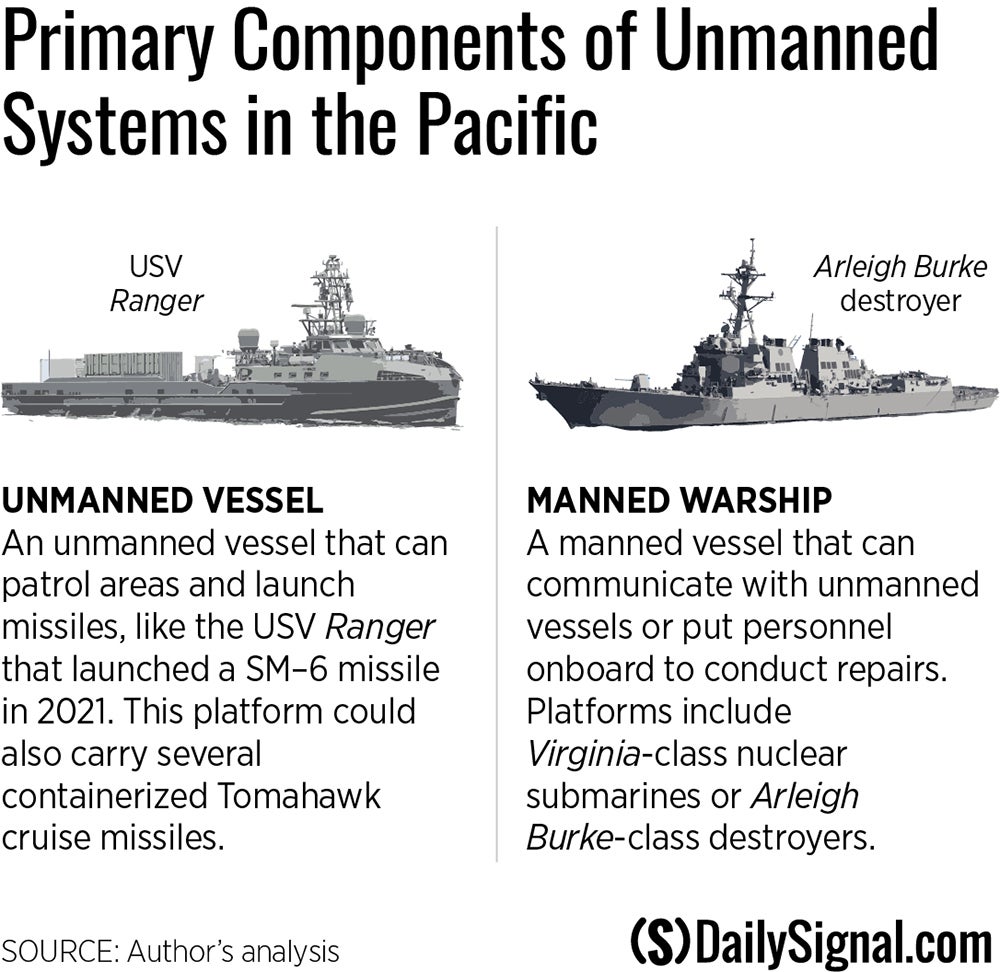

The Philippine Sea offers the most viable opportunity to shape the military balance of power—but it will also require rapid deployment of armed unmanned platforms. Inspired by Ukraine’s use of long-range drone ships with anti-air technology, the U.S. should rapidly bolster key defense and strike capabilities while complicating China’s targeting efforts. This could be done by teaming a manned warship or submarine with a group of armed unmanned ships for added stealth and survivability. Units could be optimized for air and missile defense of key bases in Guam or outfitted for long-range strike missions. Done in time and at scale, the U.S. could derail China’s 2027 military plans.

Conclusion

Ukraine’s success in the Black Sea demonstrates the importance of rapid evolution as combat conditions change. As the U.S. and allies prepare for war in the Pacific, Ukraine’s naval lessons must serve as a template that can be adapted to the realities of the Chinese threat and the geography of the western Pacific.

The post Applying Lessons From Ukraine: How to Win in the Indo-Pacific appeared first on The Daily Signal.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0