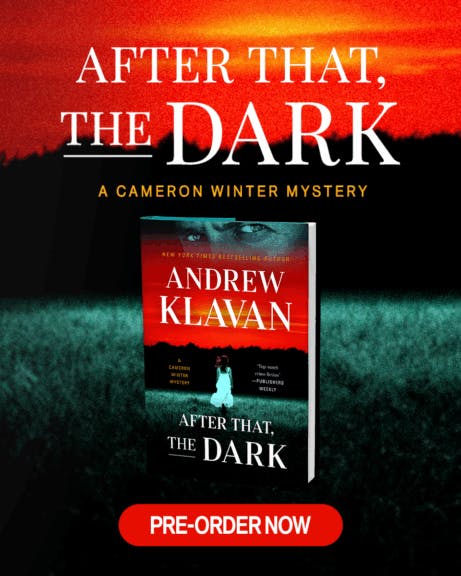

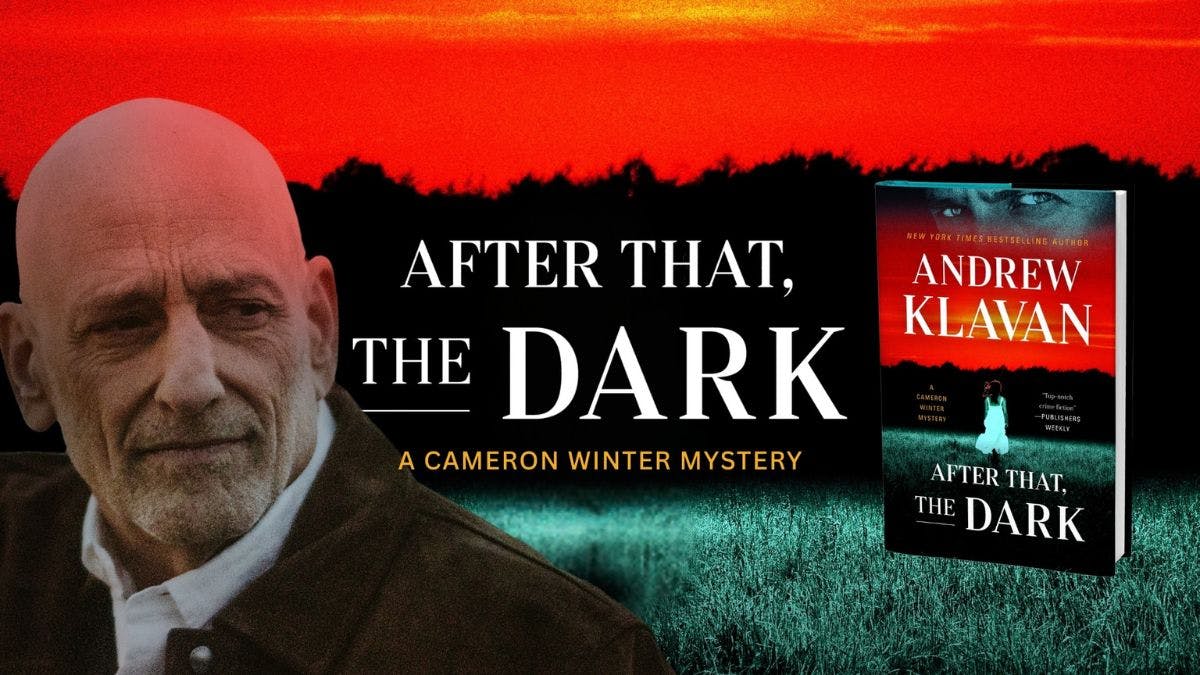

EXCERPT: Get A Sneak Peek Of Andrew Klavan’s Forthcoming Book, ‘After That, The Dark’

The following is an excerpt from Andrew Klavan’s “After That, the Dark,” which hits shelves on October 28 from Mysterious Press. Order Andrew Klavan’s new book on Amazon or pick up a signed copy at Daily Wire Shop.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

* * *

Prologue

Tilda Bach folded the laundry and thought about the devil. The sunlight at the basement window was just beginning to lose its edge of mid-day brilliance. The sun, unseen beyond the left-hand border of the long, narrow pane, had dropped behind the screen of the summer leaves. The sparse grass of the small backyard was darkening.

Tilda gazed out through the dusty glass. Her hands, moving automatically, worked a bath towel into a tidy square. She set the square down on the pile of towels atop the dryer. She reached into the plastic basket for another. But her eyes remained on the window all the while; the long, narrow window set high on the wall in front of her, just above the level of her head.

Outside, just visible at the right edge of the glass, lay the dirt path along the border of the lawn. The path led to the doorway of her husband’s storage shed.

Tilda felt sick inside at the thought of what she was about to do. But what else could she do? The devil was in her house. Or a demon sent by the devil. She didn’t pretend to know the ins and outs of such things. She didn’t even know if she really believed in such things. But she did know this. Something had gotten inside her husband. Something evil. Something alive. It was taking him

over. It was eating his soul away. It was turning him into itself.

At night, in bed, asleep, in dreams, he said things, horrible things, murmured obscenities full of violence. She woke sometimes to find him sitting in her armchair, his laptop on his thighs, the white light from the monitor shining on his face, his face demonic, twisted into a grin. Sometimes he went out at night. For a drive, he said. Sometimes he went into the shed and locked the door and did not come out for hours. It was not like him. It was not him at all. It was something else.

Whatever it was, she had to stop it. For his sake. For her sake. For the sake of the baby growing inside her.

She lay another fresh-folded towel on the pile atop the dryer. Then she stopped moving altogether. She stood there, still, gazing out the basement window. Gazing at the shed.

She knew she needed help. She had to tell someone. Someone at the church, someone who might understand. But no one would believe her unless she brought them proof. Everyone at church knew Martin. Everyone loved Martin. If she went to Pastor Mike or her friend Gretchen, the junior warden on the vestry—if she went to them and started babbling about devils and demons and evil, they would think she had gone crazy. She herself was half-afraid she had gone crazy, thinking about these things. Sometimes she was sure she had. She needed proof, proof to show the pastor, proof to show herself.

She believed the proof was hidden in that shed.

For long moments end to end, she stood motionless in front of the dryer, her arms at her sides. She went on gazing out the basement window. Finally, she drew a long deep breath. When she let it out, it trembled. The fear in her chest was a cold fire, an icy flame that made her body feel hollow and weak. She feared that it would stop her heart. She feared that it would hurt her baby.

But she could not talk herself out of her suspicions anymore.

It was getting late. She wasn’t wearing her watch, but she knew it had to be four o’clock at least. Martin had left for work early this morning, before eight. He probably wouldn’t be home for another hour or so, but she couldn’t be sure.

She had to go out there. She had to go out there now.

Tilda was a small woman, twenty-eight, thin except for the baby bump beginning to show at her center. Her lank yellow hair framed a sharp face with sharp features. As she drifted across the basement floor toward the stairs, she felt her own frailty. She felt insubstantial, like a ghost, like a piece of paper blowing on a breeze. In her flowery blouse and her sandals and her pale blue shorts with the stretchy waist to fit her growing belly. She felt as if there were nothing to her except that icy fear.

She rose up the stairs as if she were floating, as if she could not stop herself even if she wanted to. Her mouth was open. Her throat was dry. The only sound she heard was her sneakers on the steps. She felt as if she must be whimpering, but she was only whimpering inside, silently.

She came into the kitchen. She moved a stride across the withering linoleum to the backyard door. She pushed out through the screen into the heat of the day. It was odd. The houses on Linden Street were close together. She could see the Mullers’ house through the leaves of the walnut tree, not far at all, a few yards away. If she turned her head to the left, she would see Bill and Mary Weber’s place across the street, and if she looked over her right shoulder, there would be the side of Jeff and Abbey’s house with nothing but a narrow slate pathway between the wall of her own house, hers and Martin’s. Why did she feel so isolated? The late afternoon was coming on, but it was still bright daylight. Why did she feel like she was swimming in shadows? Why did she feel so utterly alone in a darkness like the dead of night?

She reached the shed. It was a worn resin box only a couple of feet taller than herself, walls of mock clapboards, dull gray. Her hand went out to it, drifting away from her as if on its own. She wanted to stop herself, but she couldn’t. She gripped the handle, pressed the latch. She drew the door open.

There was the darkness, the darkness she had felt all around her. It was waiting for her inside the shed.

She stepped into it, drawing the door shut behind her.

The shed had no windows but there were vents beneath the eaves. Some light trailed in through these, enough to see by. She found the switch on the wall and flipped it. A bare bulb glared angrily down from the low ceiling.

She swallowed hard. How could she be so close to home and so afraid? Afraid of her own husband, her own Martin. She could still remember—she would never forget—the sweetness of his smile the first time she had seen him. She was serving drinks in the Bar and Grill, a place so low it had no other name, just Bar and Grill, that’s all. The music there was so loud it had no tune but noise. The walls shook with it. She was moving down the line of customers, looking for empties she could refill. She came upon his smile among the cunning faces and the angry faces and the faces, as she now understood, of men who did not even know they had despaired. There was Martin, his sweet smile, like sudden water mellow in the midst of baking sand.

“How about you and me go somewhere quiet, darling, and talk about Jesus Christ,” he said.

He had really said that. It had made her laugh out loud. It had got her talking with him, flirting back and forth, trading lines until she’d made a date with him for after work, good-looking boy that he was, big strong man that he was, muscles outlined in the fabric of his tee, a workingman’s hands, rough and sure. She knew how it would be, but that didn’t matter. It would be the same as it always was in the end, but if it was good for even an hour, that was something, wasn’t it? A little dream of something, floating like a bubble, pink and pretty, in the air. A feeling like someone cared for her or at least thought she was pretty enough to be worth having. So she went with him, same as she always went with all of them.

Martin drove her in his pickup to the overlook by the lake, the usual lover’s lane. And there, in a surprise as shocking as a scene in a movie, as a ghost-monster jumping out through the glass of a mirror or the killer lurking in the house after the heroine rushes inside and locks the door, he had sat with her in that place of forlorn surrender and talked with her till dawn about Jesus Christ. He really had. Talked and talked about religion and the sadness of worldly things until she heard herself talking back to him, not just the usual jaded cliches, but real talk, just as the stars were fading, about the misery she pretended was “doing okay,” and the pain she had figured was just the way things were. It all came pouring out of her into his gentle eyes and she knew with a kind of childlike wonder: She had found love.

She stood where she was in the shed. She breathed unsteadily, cold with fear. Her eyes traveled over the space beneath the glaring light from the naked bulb. The red tool chest she had bought him for his birthday. The power tools hung on the wall. The shelves of paint cans and buckets and weed killer. The workbench with its segmented trays of electronic bits and pieces: black boxes and wires and glassy elements. They looked to Tilda like the bodies of some alien robots gathered up for burial after their starship crashed to earth. Martin had a genius for electronics. He could fix things, make things. Toys for poor kids at church who didn’t have any toys. Computer add-ons that could pick up the videos from nearby drones or trace what a neighbor’s computer was doing on wireless. Some of these things—Tilda wasn’t even sure they’d been invented yet. She was always telling Martin he ought to turn this skill into a business somehow. He could make real money at it. But he’d just laugh and say it was only a hobby, nothing special. Then he’d go back to rooting through the pieces splayed out over the workbench, putting them together—at random, it seemed to her—like he was a sorcerer magically transforming junk into technology.

But all those doodads were stowed away now, each in its compartment, like mashed potatoes and peas in a frozen dinner tray. Fearful as she was, Tilda almost smiled at that. For a big, shambling, sloppy boy, Martin was neat as a prissy old maid. She had always found that kind of adorable. He liked things in their proper places, all just so.

That’s why she spotted the hiding place right away.

A cardboard box stuffed with wires, shoved under the workbench where it shouldn’t have been. That was the telltale sign.

She moved to it slowly. She wasn’t sure she was breathing at all anymore. The fear had gutted her. She felt dead and empty. She knelt down. She wrestled the box to one side. She saw the rectangular gray metal chest hidden behind it. She drew it toward her. It scraped against the floor.

The chest was locked, but she knew where the key would be. She reached up and pulled open the workbench drawer, right at her eye level. There it was in the front compartment, right in its proper place. She picked the key out and, kneeling there, unlocked the chest.

Everything came on her all at once: all the horror and all the fear together.

Tilda lifted the lid of the chest and in the harsh, pitiless glare from the bare bulb she caught a single glimpse of an image—a printed picture—of pornographic brutality. Martin’s nighttime murmurings come to life. The girl’s body. The girl’s face. Her wide-eyed terror. Her mouth strapped shut. There was also a stained T-shirt, bunched in a corner of the chest. Blood—the thought was like a siren going off inside her. That’s blood!

At the same time, at the very same second, there came the sound of tires on the driveway outside. Martin’s pickup. A sound she knew well: her husband had come home.

A noise escaped her. A single, strangled cry. She shut the chest with a clanking bang. Too loud! He’d hear her. She shoved it back in place. Was it back in place? The right place? Would he notice it had been moved? She put the cardboard box in front of it again and was already rising from her knees as she dropped the key back in the workbench drawer and shut the drawer as quietly as she could. She could hear the door of Martin’s pickup opening.

The driveway was on the near side of the house. She had seconds—three or four or five, no more than that—to get out of the shed before he stepped from the pickup’s cab and saw the light shining through the vents. He may have already spotted it as he was driving up. She had no way of knowing.

Another whimpering cry came out of her as she raced to the door and hit the switch. The shed went dark. The darkness seemed to tilt and spin around her. She opened the door the slightest crack. She slipped through the gap like liquid smoke. She shut the door and started walking quickly through the afternoon sunlight. She looked up toward the driveway. An instant—half an instant—later, Martin shut the truck door and turned to see her moving toward him across the lawn.

How much had he seen? The light in the shed? The door closing? Or maybe just this, just Tilda walking toward him. Maybe she could tell him she’d heard his truck in the drive and had come out the kitchen door to greet him. Maybe. She didn’t know what he knew.

Her mind was a panicked stampede of images. That girl in the printed picture. That T-shirt stained with blood. And had she put the chest away in the right place? And was her fear visible in her eyes? And was her horror visible on her red cheeks? No way of knowing.

Tilda smiled brightly, sick at heart. She waved as she walked toward her husband. He towered over her, broad shouldered and muscular in his workingman’s tee, the underarms dark with sweat. He had his toolbox in his right hand. He was smiling over her. His sweet smile. But was he masking something? Suspicion? She couldn’t tell.

“Hey,” he said. And with his big bear-paw of a hand behind her head, he drew her up on tiptoe into a kiss. Tilda felt as if a whole world inside her was collapsing into dust.

Martin set her down and grinned and touched her belly.

“Hey there, baby,” he said to the bump there. “Daddy’s home.”

* * *

Published by permission of Mysterious Press.

Andrew Klavan is the host of “The Andrew Klavan Show” at The Daily Wire. Klavan is the bestselling author of numerous books, including the Cameron Winter Mystery series. The fifth installment, After That, The Dark, is now available for Pre-Order. Follow him on X: @andrewklavan

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0