Patriotic assimilation is the cure for America’s identity crisis

Andrew Beck has articulated a thick version of the assimilation of immigrants (rightly so, in my view), which harks back to the spirit of Americanization prevalent from America’s founding to roughly the 1960s. Louis Brandeis, a liberal and political ally of the detestable Woodrow Wilson, expressed this common idea of assimilation in his July 5, 1915, “Americanization Day Speech”:

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

What is Americanization? It manifests itself, in a superficial way, when the immigrant adopts the clothes, the manners, and the customs generally prevailing here. Far more important is the manifestation presented when he substitutes for his mother tongue the English language as the common medium of speech. But the adoption of our language, manners, and customs is only a small part of the process. To become Americanized, the change wrought must be fundamental. However great his outward conformity, the immigrant is not Americanized unless his interests and affections have become deeply rooted here. And we properly demand of the immigrants even more than this. He must be brought into complete harmony with our ideals and aspirations and cooperate with us for their attainment. Only when this has been done will he possess the national consciousness of an American.

We could characterize Americanization as the highest form of assimilation: patriotic assimilation. When an immigrant and his first-generation children leave their previous people and join the American people, it means they have an emotional attachment to our country and instinctively identify with historic America — our principles, history, and culture.

Patriotic assimilation happens when our nation’s story has become part of their inheritance as Americans.

Even though the newcomers and their children may come from China, India, Guatemala, or Norway, they embrace Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Hamilton as their ancestors. When reading about the history of the War of 1812, they identify with historic America and think, “We fought the British in 1812,” as opposed to thinking that they (white males) fought other white males 200 years ago.

Patriotic assimilation happens when our nation’s story becomes part of their inheritance as Americans.

An emblem of assimilation

In the late 19th century, Rep. Richard Guenther (R-Wis.) epitomized patriotic assimilation. Born and educated in Prussia, Guenther didn’t emigrate to America until his early 20s. He was involved in the German-American community and Republican politics in Wisconsin before being elected to Congress in 1880.

Guenther came from an ethnic subculture, but Andrew Beck would be pleased that he recognized the primacy of America’s Leitkultur.

From 1887 to 1889, America was on the verge of a war with Bismarck’s Germany over a geopolitical crisis in the Samoan Islands. Understandably, other congressmen wanted to know where Guenther and his fellow German-Americans stood. Guenther responded in this way:

We will work for our country in time of peace and fight for it in time of war. When I say our country, I mean, of course, our adopted country. I mean the United States of America. After passing through the crucible of naturalization, we are no longer Germans; we are Americans. We will fight for America whenever necessary. America, first, last, and all the time. America against Germany, America against the world; America right or wrong; always America. We are Americans.

Principled pluralism?

Andrew Beck argues that building a “giant statue depicting the monkey-faced Hindu deity Hanuman” in Sugar Land, Texas, signals a failure of Indian immigrants to assimilate into America’s culturally Christian civilization. Mark Tooley counters that Beck need not worry, since religious freedom for minorities is part of the “principled pluralism” built into the American order.

How should we address this clash between Beck’s concern over assimilation and Tooley’s defense of pluralism?

Examining the issue through the lens of patriotic assimilation, the critical question is where the ultimate political loyalty of the architects and adherents of the Hanuman statue lies. If there were a war or a lesser conflict between the United States and India, where would the Hanuman advocates stand?

Would they echo Rep. Guenther and back the United States through thick and thin? Would they resoundingly say, “Always America. We are Americans”? Or would they share the sentiments of Rep. Delia Ramirez (D-Ill.), who unabashedly stated that she’s “a proud Guatemalan before I'm an American”?

In the past, Americans from minority ethnic groups have chosen the path of patriotic assimilation affirmed by Guenther. One thinks of the German-Americans who fought Germans at the Argonne Forest in 1918, the Italian-Americans who killed Italians in Sicily in 1943, and the Japanese-Americans who fought Japan’s ally Germany throughout Europe in World War II.

Americanism: Idea or culture?

I agree with Andrew Beck, Mark Krikorian, Paul Gottfried, and James Hankins that our assimilation problem is self-imposed. The fault is with us, not with immigrants. More specifically, the “us” refers to our woke, progressive elite, which has successfully carried out a cultural revolution against historic America.

The lack of patriotic assimilation in contemporary America is, as Hankins notes, because “our public schools and cultural institutions, public and private, have embraced a new religious faith: that of multiculturalism.” He suggests undermining this new religion along with its evil siblings — diversity, equity, and inclusion, “anti-racism,” radical gender theory, and all forms of wokeism.

Krikorian, Gottfried, and Hankins all appear to hope that our schools and cultural institutions will once again transmit a patriotic civic religion to immigrants and the native-born. The American left will, of course, oppose patriotic assimilation in principle. It is no accident that the Biden administration prohibited the use of the word “assimilation” in government documents.

RELATED: National conservatism is the revolt forgotten Americans need

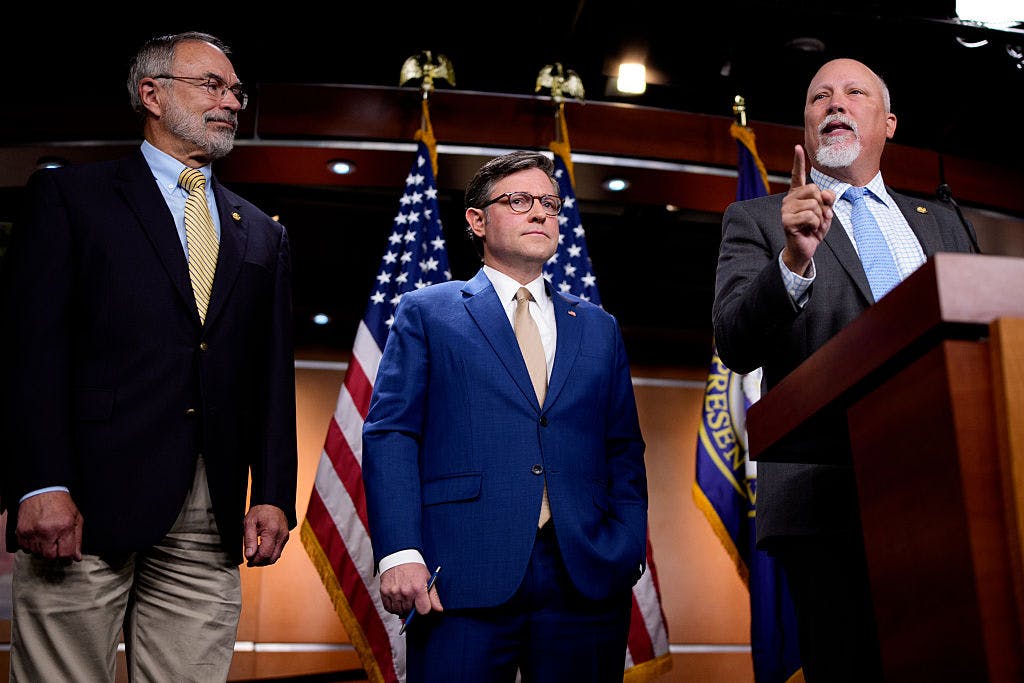

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Moreover, the question of who we are as Americans raises the issue of what exactly immigrants should be assimilating to. Does it mean assimilating to a set of universal principles and ideas or a particular people and culture? Or both? Does being an American have an ideological component?

During the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century, conservative thought leaders overemphasized the concept of America as a “proposition nation.” They taught that, unlike other countries, America was founded on ideas rather than culture or traditions. This attitude went hand in hand with support for mass immigration, coupled with little to no emphasis on assimilation. If our nation is based solely on ideas, then anyone in the world can easily become an American if they agree with them.

The American right’s overemphasis on the proposition nation narrative was a mistake.

Furthermore, liberal conservatives (today’s “FreeCons”) argued that since assimilation was successful in the days of Ellis Island, it would continue being successful. But this ignores the two main reasons assimilation worked in the early 20th century. American leaders, such as Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge, insisted on Americanization, and immigration was reduced drastically in the 1920s.

The American right’s overemphasis on the proposition nation narrative was a mistake. Not surprisingly, the American left adopted this ideological narrative and reinterpreted core American ideas as the revolutionary expansion of the progressive project, promoting DEI, LGBTQ rights, and the “fundamental transformation” of the United States.

Ideas and culture

In 2001, the eminent constitutional scholar Walter Berns wrote a magnificent monograph titled “Making Patriots.” Berns embraced America’s civic religion and affirmed the absolute necessity of a citizenship education that inculcates a “love of country” in both immigrants and the native-born and focuses on “how to transmit” that love “from one generation to the next.”

I have one crucial point of disagreement with Berns, however. He writes that American nationhood is unique because it is based “not on tradition, or loyalty to tradition, but on an appeal to abstract and universal and philosophical principles of political right.”

Because of this attachment to principled ideas, Berns asserts that Stephen Decatur, the greatest American naval hero of the early 19th century, was being somehow unpatriotic or “un-American” when he declared in a famous toast after defeating the Islamist Barbary pirates, “Our country, in her intercourse with foreign nations, may she always be right, but our country right or wrong.”

RELATED: How woke broke the country

Photo by Eric Raptosh Photography via Getty Images

Photo by Eric Raptosh Photography via Getty Images

Decatur, who served his country with extraordinary bravery and prowess in war, revealed an instinctive love of America and a concrete attachment to American nationhood. These sentiments should not be disparaged as being beyond the pale of an acceptable form of patriotism. As Montesquieu argued, an emotional attachment and instinctive love of country are necessary for any republic to survive. We could use many more Stephen Decaturs today.

I maintain that American patriotism rests on both ideas and culture. Claremont Review of Books editor Charles Kesler said correctly, “The American creed is the keystone of American national identity, but it requires a culture to sustain it.”

American nationhood has an ideological component, and there are times when ideas trump culture. Paul Gottfried notes that 18th-century American colonists were shaped by a shared culture, including the King James Bible, Shakespeare, Protestant theology, Plutarch, and the like. True, American patriots and Tories shared the same culture, but from 1776 to 1783, they killed each other over what constituted the best regime.

So what is to be done today?

First, we must mobilize the emotion-laden concepts of Americanization and patriotic assimilation. We must pit these concepts against the left’s weaponized theories of multiculturalism and diversity, which have besieged universities, schools, foundations, nonprofits, civic organizations, corporations, faith-based institutions, and all levels of government

Second, Mark Krikorian is right that we must “reduce immigration across the board,” both legal and illegal. Current levels of immigration are clearly harming the prospects of assimilation.

America faced a similar situation in the 1920s when Calvin Coolidge argued, “New arrivals should be limited to our capacity to absorb them into the ranks of good citizenship. America must be kept American.” We need to act on Coolidge’s sage advice again.

Editor’s note: A version of this article appeared originally at the American Mind.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0