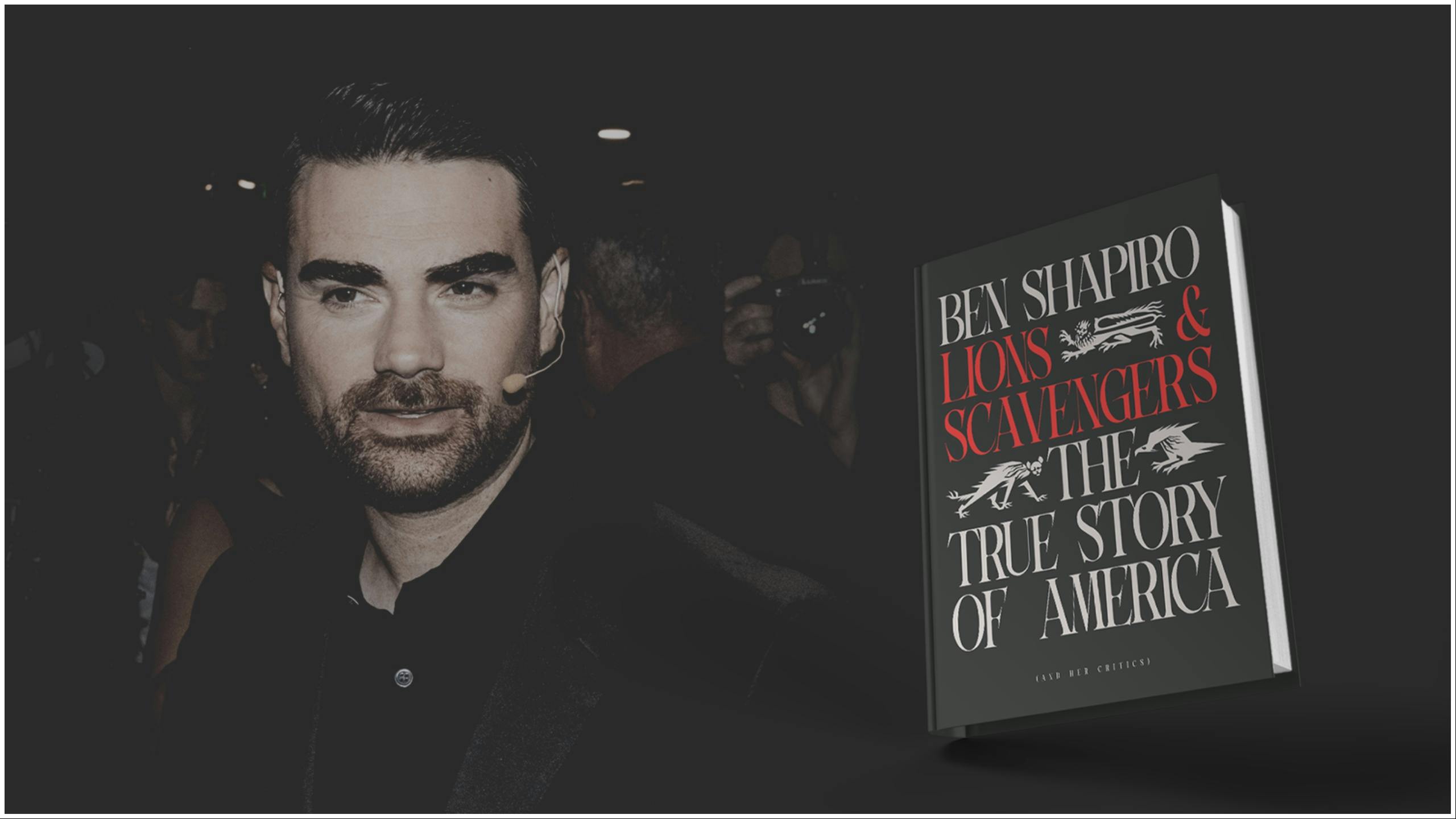

Read The Entire First Chapter Of Ben Shapiro’s Upcoming Book: ‘Lions And Scavengers’

The following excerpt is taken from “Lions and Scavengers: The True Story of America (and Her Critics),” by Ben Shapiro (Threshold Editions/Simon & Schuster, September 2, 2025)

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

* * *

CHAPTER ONE: THE WAY OF THE LION

Rome, Italy

You can feel the ghosts.

And they stir.

Italy is one of the most beautiful countries on the planet. And Rome is a treasure chest of a city. It is a city of layers: layers of history piled atop one another, a glorious and haunting archaeological tell that serves as a living city. Stroll past the Roman Colosseum, where Christians were fed to lions; under the Arch of Titus, where the Roman emperor commemorated his destruction of the city of Jerusalem; and toward St. Peter’s Basilica, where Michelangelo’s heartbreaking sculpture of a Jewish mother cradling the body of her sacrificed son still brings you to tears, centuries later.

And then make your way toward the Sistine Chapel.

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was controversial in its time. Now it has become so well-known that you would expect it to feel kitschy and overplayed.

Instead, in an age in which we have forgotten the voices of our ghosts, it speaks.

The depiction of God — that muscled Old Man in the sky — reaching down to Adam, the first man made in His image; the finger of the Divine, nearly touching the finger of man, passing into him the power of creation, the unique power of man to shape the world in which he lives; the knowledge that with that power comes both risk and opportunity. That gap between the fingers of God and Adam — some three-quarters of an inch — reminds us that while man is made in God’s image, he can never reach God’s perfection, and that man’s understanding and God’s remain forever separate.

The Creation of Man lies at the root of our civilization.

For in creating man, God gave him both power and responsibility.

On this day, we are taping in the ruins of Ostia.

Our company, The Daily Wire, has commissioned a series on the ideas and history of Western civilization, starring Jordan Peterson. Jordan has taped with me in ancient Jerusalem; with religious symbolist Jonathan Pageau on the Via Dolorosa; with philosophy scholar Spencer Klavan in Athens; and with Bishop Robert Barron in Rome.

Today we are to sit together and speak about the big ideas of the West: the things that make the West unique. The history of the city goes back centuries before the birth of Christ; the ruins that can be viewed today date back to the third century BC. Ostia became a vital port for the Roman republic. But Ostia became most famous for her part in the religious awakening of St. Augustine. In his Confessions, Augustine writes of speaking with his mother near the day of her death, in a garden in Ostia, probably within sight of where we now talk. Nearly two millennia later, we are in the city of Augustine, separated only by the passing breath of time.

It is cool as the sunlight diminishes; in the quiet of the burgeoning evening, we discuss the value of revealed religion and Greek reason, of ritual and ideal, of the communal and the individual. Citations of Aristotle and Augustine and Maimonides and Kant fill the round. It’s exciting and wonderful and joyous. It makes me think of the Socratic notion that a good afterlife lies in an eternal search for “true and false knowledge; as in this world, so also in the next.”

The arena is empty, but the voices reverberate.

These are ideas that feel new, even though they have been put aside or forgotten in favor of glib existentialism or ironic nihilism or resigned determinism. These are the ideas that formed the civilization that brought us everything from private property to the moon landing, everything from democracy to modern medicine.

These are ideas with meaning.

As the sun sets, we walk back to our cars, thinking about the ideas that have animated a civilization. Later we’ll meet up for dinner, talk about those ideas long into the evening.

But as we walk back to our cars, the site is quiet.

We all feel the weight of Western civilization. Rome and Greece and Jerusalem and London and Washington; Tours and Lepanto and Vienna; the profane and the holy, the violence and the peace, the bank and the cathedral — you can feel them all.

Mostly what you feel is the ghosts.

The ghosts of the Lions.

And they stir.

Order your Signed Copy of “LIONS AND SCAVENGERS” today, EXCLUSIVELY in the Daily Wire Shop

PHILOSOPHY OF THE LION

Lions have a philosophy — a deceptively simple one.

Often, it is not held as a philosophy, but rather as a way of life. Few Lions spend time thinking about the deep roots of their actions in the world. They act in the world as Lions, confidently and without compromise or apology. Ask them their philosophy, and they may laugh at you — they know, deep in their bones, what it is they believe, even if they cannot articulate it.

It does not take a philosopher to be a Lion.

Yet Lions do have an unstated, implicit philosophy, a set of principles by which they live. It is a philosophy developed over the ages, handed down father to son and mother to daughter, a chain of teaching stretching back thousands of years. That philosophy can be summed up in the contrast and symbiosis between Jerusalem and Athens. Jerusalem, in the typical philosophical parlance, represents faith and revelation; Athens represents reason and logic. One could write an entire book on the interplay between Jerusalem and Athens (in fact, I did — check out The Right Side of History for a more comprehensive investigation into the topic).

To boil down that broad philosophical investigation, however, the philosophy of the Lion is based on three central principles:

- There is a master plan, a Logos behind the universe.

- You are made in the image of God.

- You have true and meaningful moral duties in this world.

The First Principle of the Lion: There Is a Master Plan

In the time of the ancients, man was seen as a mere victim of the conspiratorial gods. In The Iliad, human characters do their best to wage war and make love, to forge peace and protect their friends — but all their actions are thwarted or dictated secretly by this cadre of higher beings, with their own corrupt motivations.

This divine conspiracy theory is enervating (and, as we will see, it is still quite commonly held). If you have no actual way to navigate a chaotic world controlled by external forces, resignation is the most plausible response. As Achilles tells Priam, whose sons have been slaughtered at the hands of the Greeks, “So the immortals spun our lives that we, we wretched men live on to bear such torments — the gods live free of sorrows.”

The pagan outlook leaves us with an inevitable choice between stoic resignation, depressive acknowledgment, and impotent rage. If we are simply buffeted by the whims of the gods, there isn’t all that much we can do about it. In this vision, we are all inescapably weak and powerless, searching among the ruins for our daily bread. In the words of Gloucester in King Lear, “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; They kill us for their sport.”

By contrast, the First Principle — that there is a logic to the universe — lies at the heart of biblical thinking. It springs from the rejection of chaotic paganism. The biblical worldview says that God stands at the heart of creation: that there is a Master Planner who stands behind the world, that the world we inhabit is His creation — and that God himself is unendingly concerned with our lives and our fates. In the biblical vision, God is the source of all things — but He is good, and so is His world.

This First Principle — the understandability of the universe — cannot be proven by science. During the early nineteenth century, so the story goes, French astronomer Pierre-Simon de Laplace was having a conversation with French Emperor Napoleon, explaining to him his theory of the beginnings of the universe. “Where does God fit into all this?” Napoleon supposedly asked. “I have no need of such a hypothesis,” de Laplace replied.

But de Laplace was wrong. Ironically enough, the starting point of science is the totally unprovable precept that the universe is understandable and logical. Without an understandable universe of predictable rules, searching for such rules would be a waste of time. That was Isaac Newton’s point when he stated, “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being. This Being governs all things, not as the soul of the world, but as Lord over all.”

This does not mean that God’s physical intervention is required to move the spheres, as ancient and medieval philosophers believed. It means simply that the very notion of a causal universe of discernable rules is a faith assumption — and that anyone who seeks answers in the universe relies on that assumption, whether explicitly or implicitly. Those who proclaim the uselessness of the Divine rely on the Divine in order to define their own purpose in life.

Every thriving civilization has a foundation in the First Principle.

It is upon that foundation that Lions build.

Lions build, because they know that there is a foundation upon which to do so.

The Second Principle of the Lion: You Are Made in the Image of God

The Second Principle — that man has personal capability — again stems from biblical thinking. Other cultures had vested great leaders with the power of creativity and choice — epic heroes and kings were given freedom of action, but the common man was either ignored or treated as a plaything of the fates. The Bible, however, devolved authority and responsibility to each and every human being. Genesis 1:27 dictates, “God created man in His image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.” What does it mean to be created in the image of God? It means to be stamped with the attribute that makes God unique: the capacity to take creative action in the world. This is the message of the story of Cain and Abel, in which God tests Cain by rejecting his sacrifice and accepting Abel’s. God asks Cain, “Why are you angry? And why has your face fallen? Surely, if you do right, there is uplift. But if you do not do right, sin crouches at the door. Its urge is toward you, but you can master it.”

In the world of the biblical God, in short, man is capable of choice. His success and failures are, in the main, on his own head. God is not a conspiratorial force; God is good, and so is the universe that He created, even if it is filled with difficulty and pain. To thrive in the face of the challenges we face makes us a success; to blame others or nature or God is to fail to live up to our humanity. As Moses tells the Jews in Deuteronomy:

See, I set before you today life and prosperity, death and destruction. For I command you today to love the Lord, your God, to walk in obedience to him, and to keep his commands, decrees and laws. . . . Now choose life, so that you and your children may live.

This principle — the capacity and responsibility of men and women — is deeply embedded in Greek thought as well. Plato stated, “[M]anaging, ruling, and deliberating, and all such things — could we justly attribute them to anything other than a soul and assert that they are peculiar to it? . . . Further, what about living? Shall we not say that it is the work of a soul?” To the biblical admonition to choose wisely, the Greeks added the importance of acting rationally: As Aristotle suggested, “the work of a human being is an activity of soul in accord with reason.”

Lions act with deliberation and reason.

Lions understand and shoulder their power of choice.

Order your Signed Copy of “LIONS AND SCAVENGERS” today, EXCLUSIVELY in the Daily Wire Shop

The Third Principle of the Lion: You Have Moral Duties

The Third Principle — that we have a defined moral duty, a purpose in the world that is not our own and that we inherit — is the final piece of the philosophy of the Lion. The Lion understands that we do not create our own moral system; that our very identity represents the intersection of personal autonomy and external duties we owe to God and one another.

The Lion knows that there are objective moral duties in the world, proper ways of acting. Again, this is implicit in the biblical worldview: God gives us commandments because there is a right and there is a wrong. The Bible does not believe in a morally relativistic universe in which men decide what is good in their own eyes. The book of Proverbs states, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; fools despise wisdom and discipline. My son, heed the discipline of your father, and do not forsake the instruction of your mother.”

The West relies not on free-floating reason in matters of morality, but on received tradition. Society, says eighteenth-century British philosopher and politician Edmund Burke, is indeed a contract, but it is not a contract between freewheeling atomistic individuals who come together only for some designated purpose from some phantom state of nature. Society is, instead, the result of rules and rights evolved over the course of generations — and this means we are bound to act rightly by a set of morals that precedes and will long outlast us:

[Society and the state are] to be looked on with other reverence; because it is not a partnership in things subservient only to the gross animal existence of a temporary and perishable nature. It is a partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.

This does not mean that the rules of a society must never change, or that the Third Principle demands fundamentalist theocracy. After all, every moral principle requires interpretation. But it does mean that morality must be pegged to something beyond the malleable reason of individuals. This means respect for moral tradition. G. K. Chesterton explained the concept with something that came to be known as Chesterton’s fence; foolish reformers see a fence in a field and, not knowing what it is, quickly demand its removal. The intelligent reformer, says Chesterton, answers,

“If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, we you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

We in the West are recipients of a moral tradition. That tradition has proved its value over the course of millennia. One need not be a God-believer to recognize this truth — or to recognize the value of that tradition. As economist Thomas Sowell writes in his masterwork, Knowledge and Decisions, “History is a vast storehouse of experience from generations and centuries past. So are traditions which distill the experiences of millions of other human beings over millennia of time.”

Even myth can act as a transmitter of effective wisdom, says Sowell: “Science is no more certain to be correct than is myth. Many scientific theories have been proven wrong by scientific methods, while great enduring beliefs which have achieved the status of myths usually contain some important — if partial — truth.” Or as Friedrich A. Hayek writes, men use tools called “‘traditions’ and ‘institutions’ . . . because they are available to him as a product of cumulative growth without ever having been designed by any one mind.” And neither Sowell nor Hayek could properly be called a biblical believer.

In the viewpoints of both Jerusalem and Athens, acting consonant with moral duty is the obligation of a human being, and brings with it fulfillment. As King Solomon says in Ecclesiastes, “The sum of the matter, when all is said and done: Revere God and observe His commandments!” Both Plato and Aristotle believed in the natural law: that nature itself was designed toward a telos, an end, by an underlying logic, a Logos. To achieve happiness was to order oneself in coordination with the universe through the use of reason. This was Plato’s answer to the challenge of Glaucon, who asked why a person ought to bother being moral: Human beings are improperly ordered if they act immorally.

Lions fulfill their purpose. As Aristotle put it, “What, then, prevents one from calling happy someone who is active in accord with complete virtue and who is adequately equipped with external goods, not for any chance time but in a complete life?” Virtue can only be instilled through practice. Some are born with fewer temptations toward sin; they are certainly lucky. But everyone has the capacity to cultivate virtue. This is Adam’s first task in the Garden of Eden: to “serve it and to guard it.”

Virtue does not grow wild. It must be cultivated.

Whether building or destroying, Lions take responsibility for their actions.

Ethics of the Fathers teaches, “In a place where there are no men, strive to be a man.”

We are all called to the work. Rudyard Kipling writes in his poem “The Glory of the Garden”:

There’s not a pair of legs so thin, there’s not a head so thick,

There’s not a hand so weak and white, nor yet a heart so sick,

But it can find some needful job that’s crying to be done,

For the Glory of the Garden glorifieth everyone.

To sacrifice in the name of cultivating the garden, no matter your personal feelings, in spite of your own interests — this is the way of the Lion.

In August Wilson’s play Fences, Troy — a disappointed former Negro League star relegated because of racial discrimination to life as a blue-collar garbageman — is confronted by his son, Cory. Troy and Cory constantly butt heads, particularly because Troy opposes Cory’s desire to seek a football scholarship. In the most memorable scene in the play, Cory demands to know why Troy doesn’t like him. Troy’s answer is a perfect embodiment of the Third Principle:

Like you? I go out of here every morning . . . bust my butt . . .putting up with them crackers every day . . . cause I like you? You about the biggest fool I ever saw. It’s my job. It’s my responsibility! You understand that? A man got to take care of his family. You live in my house . . . sleep you behind on my bedclothes . . . fill you belly up with my food . . . cause you my son. You my flesh and blood. Not cause I like you! Cause it’s my duty to take care of you. I owe a responsibility to you. . . .Don’t you try and go through life worry about if somebody like you or not. You best be making sure they doing right by you.

Of course, one could describe fulfillment of the Third Principle as love. As Golde sings in Fiddler on the Roof when asked by her husband, Topol, whether she loves him, “For twenty-five years I’ve lived with him / Fought with him, starved with him . . . If that’s not love, what is?”

Duty is love, and love duty.

In Hebrew, the word for love is written אהבה. The root of the word is הב — to give. Love and duty are not merely intertwined; they are one and the same. The book of John makes the same point: “Greater love hath no man than this: that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

We have no greater love than to live our lives for our friends, our family, our children, and our civilization.

The world is a place filled with those who shirk duty, who blame the world for their own failures. In that world, the Lions are those who do the opposite: They take the load upon their own shoulders. They bear the burden and reap the rewards of that task. They look in the mirror and ask, “What more can I do?”

While visiting Jerusalem, I prayed next to a twenty-one-year-old soldier in the Israel Defense Forces, or IDF.

He was a kid — closer to the age of my ten-year-old daughter than to my age — and yet he had been called to serve. While in Gaza fighting Hamas, he had been gravely wounded in an explosion in Zeitoun; he’d been airlifted to Soroka Medical Center, where both of his legs had been removed, as well as one hand. Doctors placed him in a medically induced coma, where he remained for two months.

After praying next to this young hero, I turned to leave. He tapped me on the arm — from his motorized wheelchair — and asked, “I have a question, Ben.”

I nodded and gestured for him to go on.

“How else can I help?” he asked. “What’s your advice for what more I can do?”

This attitude isn’t unique to Israel, of course. It’s the attitude of every parent who goes the extra mile, every worker who stays the extra hour, and every Western soldier who looks into the face of evil and mounts up. It is the message of Isaiah when he takes up the challenge of God:

Then I heard the voice of my Sovereign saying, “Whom shall I send? Who will go for us?”

And I said, “Here I am; send me.”

These are the Lions.

The philosophy of the Lion is clear and direct and good :

There is a logic to the universe.

You are created in the image of God, which means that you have the creative power to choose — and that means you have responsibility for your choices.

The world is a place filled with moral duties — duties that spring not from your own desires and feelings, but from God, from tradition, and from reason. Fulfill those duties and you will fill your life with meaning.

All of this presupposes a society.

But who are the Lions who comprise this society, this civilization?

We turn to that question next.

* * *

The following excerpt is taken from “Lions and Scavengers: The True Story of America (and Her Critics),” by Ben Shapiro (Threshold Editions/Simon & Schuster, September 2, 2025)

Published by permission of Threshold Editions/Simon & Schuster.

* * *

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0