Supreme Court Delays Delegation’s Reckoning for Another Day

The Supreme Court punctuated its 2024 term with a decision that allowed the Federal Communications Commission to continue charging Americans billions of dollars annually for its Universal Service program. Universal Service, a subsidy program meant to bring communications technologies to rural and low-income areas, survived a consumer group’s challenge which argued that the FCC’s seemingly limitless power to raise funds for universal service was an unlawful delegation of Congress’s taxing authority to the executive branch.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

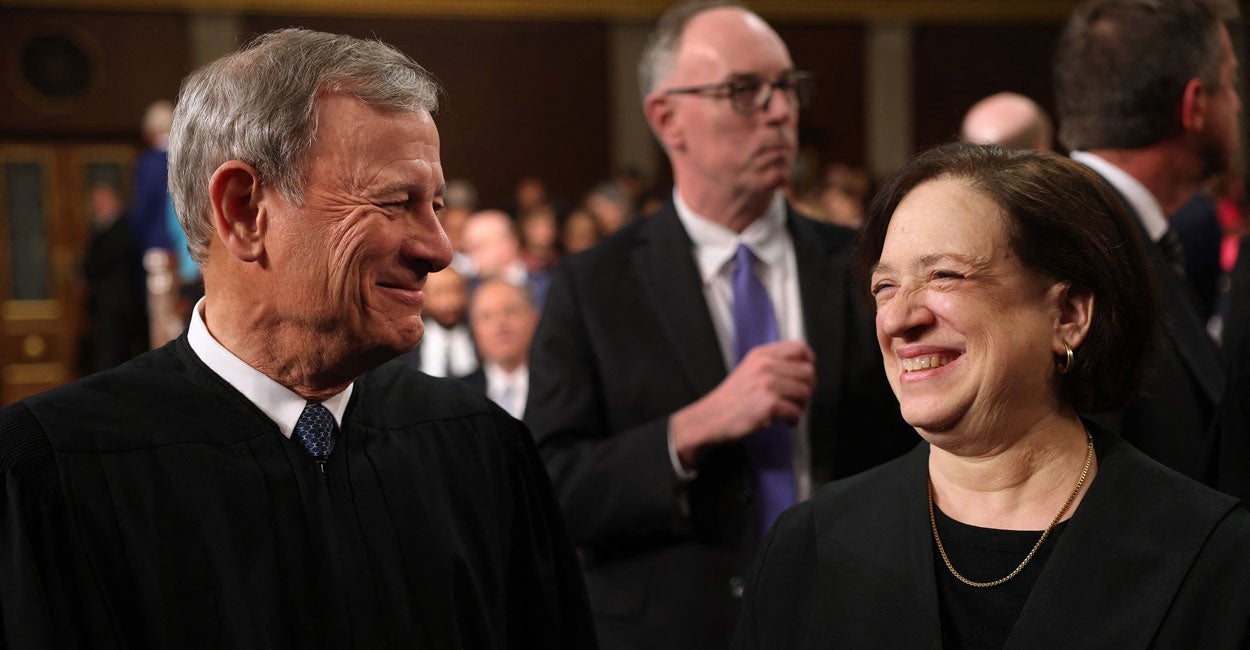

The decision in Federal Communications Commission v. Consumers’ Research causes little surprise given the tenor of oral arguments in March, but it will cause even less celebration as the Roberts Court backs away from another opportunity to restore a vital separation between the federal branches.

If we can know a doctrine by its fruits, then the Universal Service program is a vivid illustration of what comes from the Supreme Court’s long-standing refusal to enforce the nondelegation doctrine, a constitutional limit rooted in the separation of powers that prevents Congress from giving the executive branch legislative authority. Universal Service has nearly doubled in annual cost when adjusted for inflation, weighing in at $8.59 billion annually as of 2024. And, as the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals noted in its earlier ruling, much of that increase inflating consumers’ phone bills is driven by the fraud and waste endemic to the program.

The growing costs, whether productive or not, have long been attributed to Congress’s failure to give meaningful guidance when it deputized the FCC to pursue “universal service.” But the Supreme Court, led by Justice Elena Kagan, declined to draw that conclusion. Instead, she and five colleagues peered into the thicket of statutory verbiage surrounding the Universal Service program and concluded that however tangled, conflicting, and even meaningless those words might be, Congress nonetheless provided an intelligible principle adequate to excuse, if not constrain, the FCC’s exercise of taxing authority.

The case centered on the 1996 Telecommunications Act, in which Congress tried to recreate a system of subsidies for underserved markets that had prevailed when the old Bell System exercised a regulated monopoly of telecoms. To do so, Congress charged the FCC with extracting “contributions” from telecoms carriers, who pass the cost on to their customers. Assisting the FCC was a nominally private body of industry representatives called the Universal Service Administrative Company, which determined the contribution factor used to calculate a carrier’s contribution.

The program faced numerous legal challenges. But not until 2023 did it meet with a setback. In 2023, the Fifth Circuit found the hybrid delegation to the FCC and Universal Service Administrative Company constitutionally suspect. It held that the compulsory “contributions” forced from telecom carriers were a tax and that because of the way the FCC defers to the industry representatives’ recommendations, “as a practical matter, [the Universal Service Administrative Company] sets the [universal service] tax.” In the Fifth Circuit’s eyes, what made the delegation unconstitutional was “the combination of Congress’s sweeping delegation to FCC and FCC’s unauthorized subdelegation” to the Universal Service Administrative Company.

The Supreme Court has not struck down an act of Congress on nondelegation grounds since 1935. And Consumers’ Research never asked the Court to overturn the mid-20th century cases that have defined the Court’s nondelegation jurisprudence. Thus, despite the Fifth Circuit’s favorable ruling, the challengers’ odds of success were always long. Before the Court, the question was simply whether Congress gave the FCC an intelligible principle (i.e., standards and limitations) to guide the FCC’s implementation pursuit of universal service.

In her majority opinion, Kagan rejected the argument that Congress must set a quantitative limit on all revenue-raising programs like universal service, dismissing this as a separate test unwarranted by the Court’s prior decisions. In fairness, it is not clear that requiring a quantitative limit amounted to a separate test rather than a specific application of the intelligible principle test to agencies raising revenue.

Still, Kagan reasoned that quantitative limits alone would not answer the nondelegation concerns. What, for instance, if Congress set a cap of up to $5 trillion? Though literally a cap, that would hardly be a limitation.

In Kagan’s view, Congress’s qualitative limits were constitutionally adequate. For instance, by stating that the FCC should raise “sufficient” funds to ensure universal service, Congress had, in Kagan’s view, set both “a floor and a ceiling” to the FCC’s revenue raising. Of course, that limitation might prove illusory if the concept of universal service were undefined. But Congress, she said, saw to that issue too, marking out further qualitative boundaries on universal service by providing the FCC with factors that it should consider like affordability, comparability of services across markets, equitable rates of contribution, and giving priority to schools and hospitals.

Though far from self-applying, one might look at this mélange and conclude that there are limits, however faint, that the FCC should observe. Even the Fifth Circuit stopped short of declaring that this mixture was contentless.

Still, the majority’s reasons are hardly unassailable. Justice Neil Gorsuch found them unpersuasive and was joined in that assessment by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. The dissenters disagreed with the majority over whether the slew of factors that Congress wrote into the 1996 Act are binding on the FCC’s determination. Kagan read the law to say that they are, but as Gorsuch pointed out, the 1996 Act only requires the FCC to consider certain factors; it never mandates that each factor be met. Instead, when the law’s grab-bag of principles points to conflicting solutions, the FCC alone chooses which principles it will implement.

Adding to the dispute, the dissenting Justices viewed Congress’s concept of universal service as far less determinate. Gorsuch argued that universal service has “no established meaning.” The concept has, in fact, proven malleable in the extreme, as illustrated by the FCC’s recent announcement that it will put Wi-Fi on school buses under the universal service program’s auspices.

Moreover, Gorsuch found it telling that Kagan et al. relegated to a footnote two provisions of the 1996 Act that empowered the FCC to fund “advanced” and “additional” services, lest these horizon-chasing goals disturb the majority’s staider reading of the law. Gorsuch suggested that the move, however subtle, “marks the first time in a long time that the Court has confronted a statutory delegation and found no way to save it.”

Finally, Gorsuch pushed back against the notion that an exorbitantly high quantitative limit could serve no constitutional function: If Congress chose a $5 trillion cap, then “the American people would at least know whom to thank when the corresponding charges showed up.” As things stand, blame for the program’s inflating costs might belong to any combination of Congress, the FCC, and/or the Universal Service Administrative Company.

It has been 90 years and counting since the Court last deployed the nondelegation doctrine to strike down a law. The doctrine’s presence has been felt on the periphery of more recent cases where the Court read statutes to narrow the sphere of executive authority. Still, a case in which the Court actually summons the courage to administer the hard medicine remains elusive.

Of course, the Court is not solely or even primarily responsible for the problem of excessive delegations. Congress could at least address the matter prospectively by legislating in more precise terms. But the excitement that greets every nondelegation case, and the legal community’s anticipation of each ruling on the question, indicates the widespread belief that delegation is yet another problem that Congress will not solve.

The post Supreme Court Delays Delegation’s Reckoning for Another Day appeared first on The Daily Signal.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0