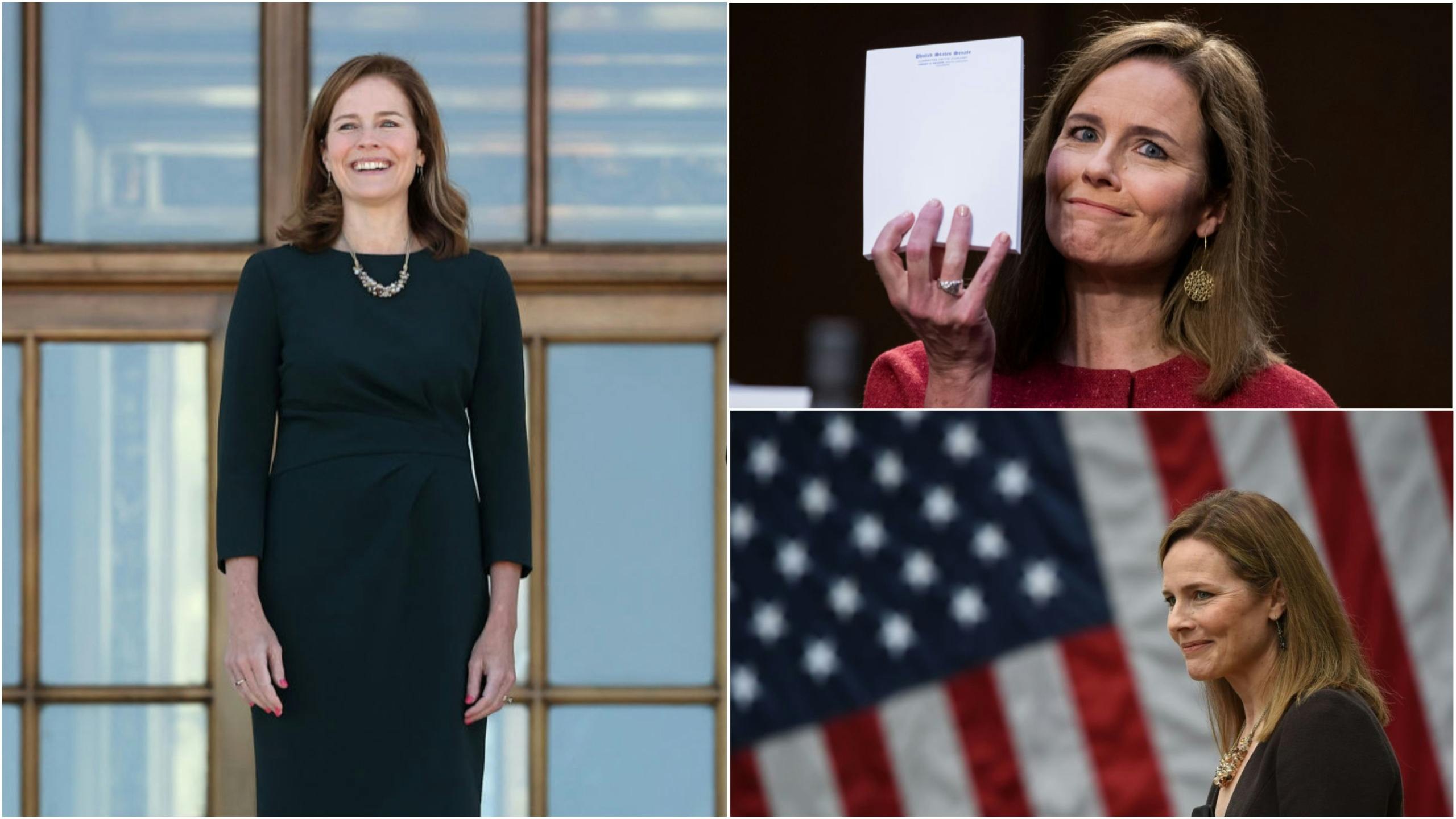

The Dogma Still Lives Loudly: Amy Coney Barrett And The Witness Of Women Of Faith

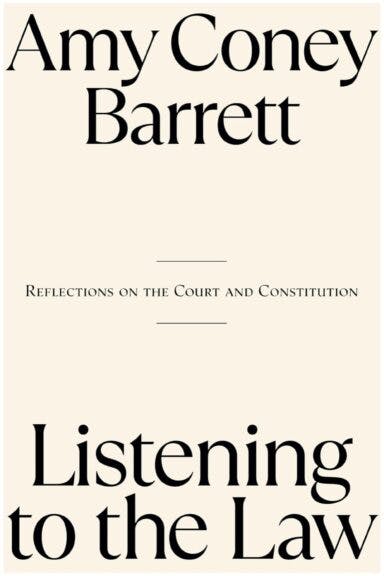

Legacy media made another feeble attempt to malign Justice Amy Coney Barrett on the eve of the release of her new book. But contrary to the whispers of palace intrigue surrounding the Court’s Dobbs decision, her book, “Listening to the Law,” is a window into the careful legal reasoning and conscientious commitment to the law that has defined her career. It reminds us that liberty depends on intellect, conscience, and the steady moral vision women of faith uniquely bring to public life. Barrett embodies these traits, and they are mirrored in women across the country who refuse to be cowed.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

Barrett’s convictions never wavered when she was maligned for her Catholic faith. During her Seventh Circuit confirmation, Senator Dianne Feinstein warned of the “dogma living loudly” in Barrett — a jab she met with intelligence, poise, and unflinching calm. Her Supreme Court confirmation displayed the same razor-sharp clarity. While many American women see in Barrett traits they recognize in themselves — dedication, moral clarity, and attention to conscience — there will only ever be one ACB. I recognized it in small, ordinary ways, too. A friend once gave me a coffee mug that read, “The Dogma Lives Loudly Within Me”—a playful badge of honor. Even when the mug was accidentally shattered by a child unloading the dishwasher, the sentiment remained intact, much like the enduring faith of women who live their convictions quietly but resolutely, holding conscience above convenience.

In “Listening to the Law,” Barrett reflects on family, faith, and the role of law in society. She recalls her great-grandmother, a widowed mother of thirteen during the Depression, noting that “No generation starts afresh; each is shaped by its predecessors.”

She observes that “Law is but one piece of what it takes to make a healthy society, and it (like everything else in life) exists in the midst of relationships.” She underscores that the Constitution commits us to pluralism through protections like those guaranteed by the First Amendment, which “requires the government to tolerate all opinions and all religions.” To critics who “suggest that people of faith have a particularly difficult time following the law rather than their moral views,” Barrett reiterates her understanding that “the guiding principle in every case is what the law requires, not what aligns with the judge’s own concept of justice.” Such resolve, she shows, can be met exactly because of the humility that derives from faith. And her own grounding in a large, loving family shines through — the book is dedicated simply to “Jesse,” her husband — a tribute both understated and profound.

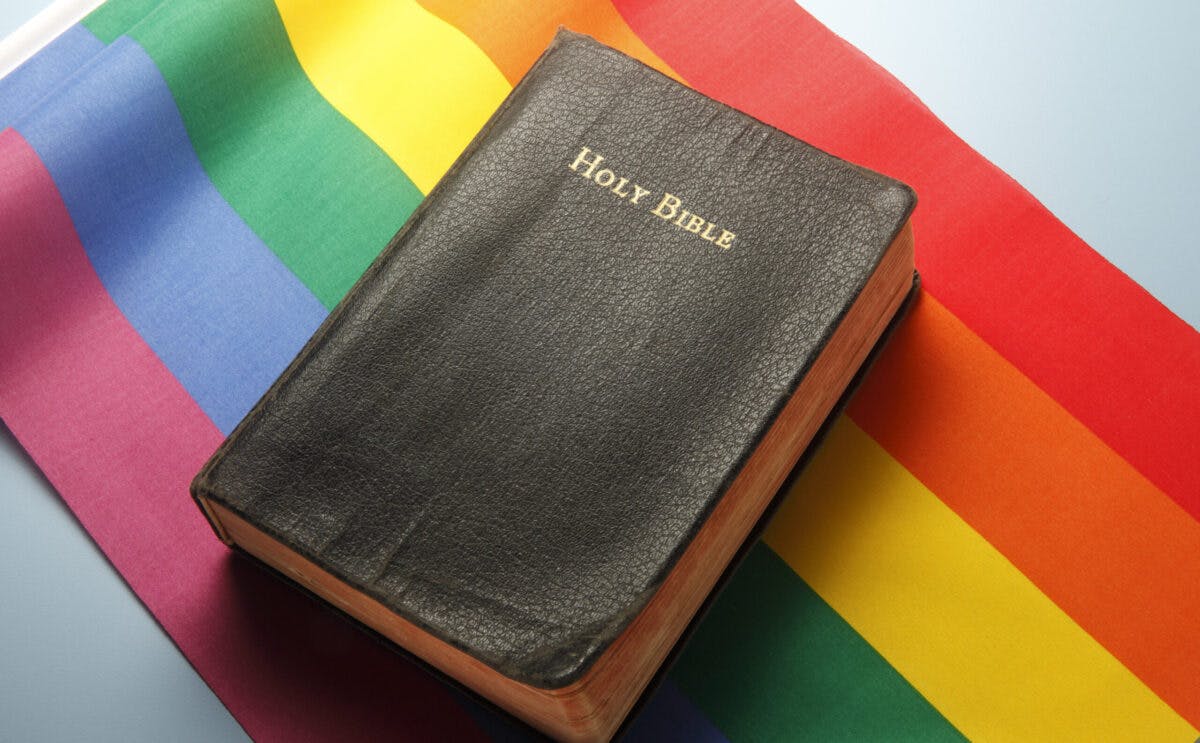

When it comes to safeguarding America’s first freedom, Barrett’s rigor is urgently needed. Sooner rather than later, the Supreme Court will revisit Employment Division v. Smith. Authored by Justice Antonin Scalia, for whom Barrett clerked, Smith held that sincerely held religious objections do not exempt people from complying with “neutral and generally applicable laws.”

In practice, Smith has often crushed religious liberty, particularly regarding anti-discrimination laws tied to sexual orientation and gender identity. Barrett’s careful attention to conscience — the “feminine genius” St. John Paul II celebrated—is precisely what the Court needs to craft a workable framework for protecting the free exercise rights of those whose beliefs are countercultural. The stakes are far from abstract: the religious convictions of real women hang in the judicial balance.

Consider Cathy Miller, a Christian baker from California, fined for refusing to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex marriage, who has asked the Court to hear her case this term. Or the Little Sisters of the Poor, who still refuse to include abortifacients or contraceptives in their health care plans despite the authoritarian demands of the Affordable Care Act’s “contraceptive mandate,” holding fast to Church teaching. Lori Smith, a Colorado website designer, refused to create speech she did not believe in — and won at the Supreme Court. Jessica Bates, a widowed Oregon mother, was blocked from fostering children because she would not embrace gender ideology — until the Ninth Circuit, of all places, vindicated her. These women were not seeking to impose beliefs on others, but to defend the right of all Americans to live out their faith without government coercion. They stand as sentinels between the state and the citizen’s conscience.

Backing them are brilliant women lawyers and scholars who turn principle into action. Kristen Waggoner, former president of Alliance Defending Freedom, has argued multiple Supreme Court cases. Lori Windham of the Becket Fund shields institutions and individuals from government overreach. Legal scholars like Mary Ann Glendon, Nicole Garnett, Helen Alvaré, and Stephanie Barclay provide indispensable intellectual firepower. Protecting religious liberty is neither abstract nor optional. It demands moral clarity, expert advocacy, and strategic rigor.

“Listening to the Law” shows that defending liberty requires both intellect and conscience. Barrett’s reflections illuminate the careful reasoning and moral clarity she brings to public life. Just as the other women highlighted here confront cultural and legal pressures with courage and fidelity, Barrett’s reflections on the law remind us that protecting religious freedom — our First Freedom — depends on women of faith. Through courage, attention to conscience, and steadfast commitment to the common good and the rule of law, they ensure liberty endures for generations to come.

* * *

Andrea Picciotti-Bayer is Director of the Conscience Project.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0