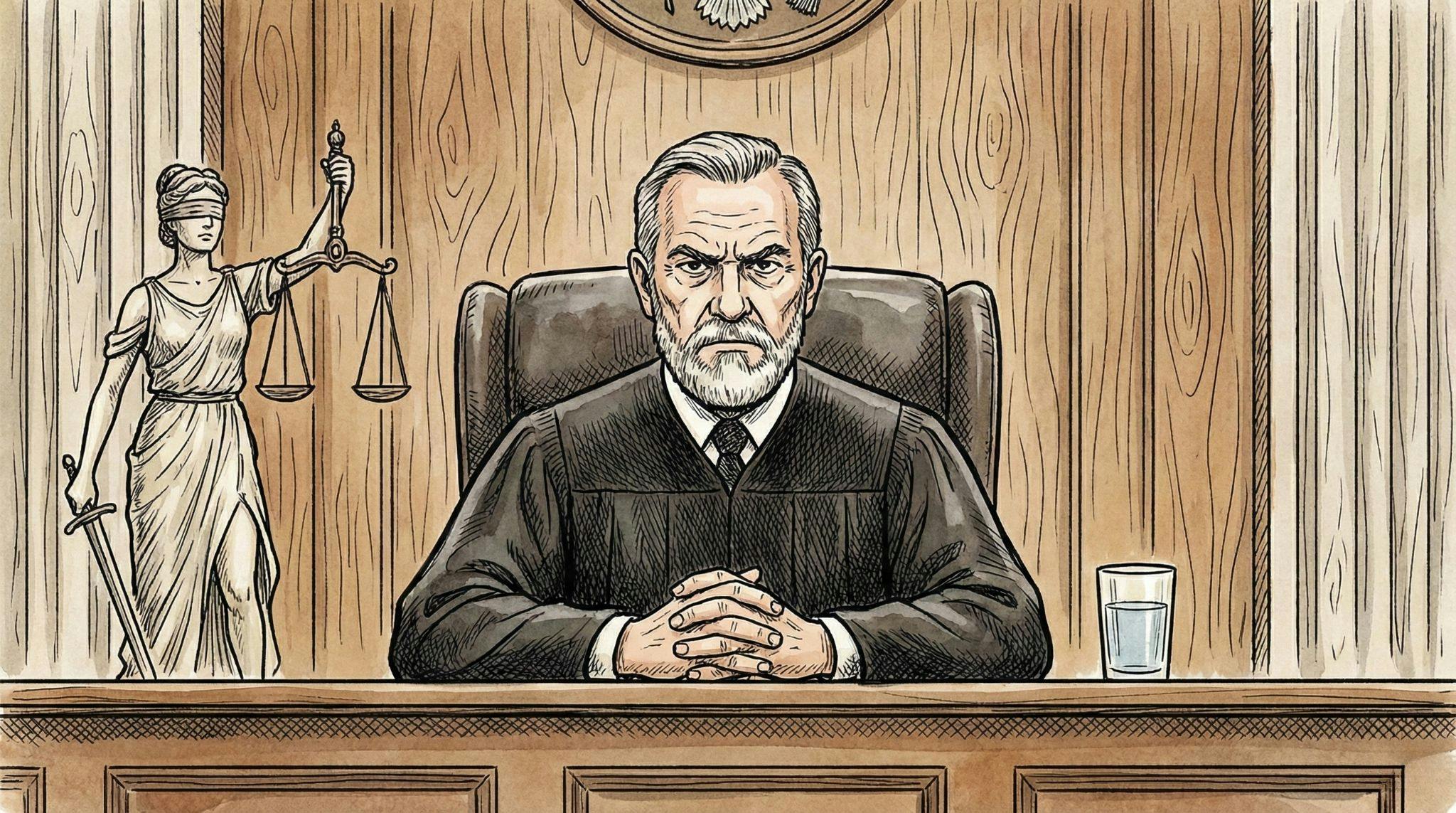

The Fifth Circuit cracks down on the asylum excuse factory

For nearly three decades, Washington has insisted that America’s immigration chaos stems from outdated laws, insufficient authority, or humanitarian necessity.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

Last week, the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals shattered that narrative.

For the first time in decades, a federal court treated immigration law as law, not a suggestion.

In Buenrostro-Mendez v. Bondi, a divided panel did something radical by modern standards: It enforced immigration law as Congress wrote it. The result ranks as one of the most consequential immigration rulings in a generation — and a direct rebuke to the legal fiction that has shielded millions of illegal aliens from mandatory detention for decades.

What the court actually said

The case turned on a simple question with enormous consequences: Do illegal aliens who entered the United States unlawfully — often years ago, without inspection or lawful admission — get discretionary bond hearings while in removal proceedings?

The Fifth Circuit answered no.

Writing for the majority, Judge Edith H. Jones, joined by Judge Stuart Kyle Duncan, held that any alien present in the United States who has not been lawfully admitted is, by statute, an “applicant for admission.” Congress supplied that definition in 1996.

Under the law, applicants for admission who cannot show they are “clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to be admitted” shall be detained pending removal proceedings.

“Shall” means mandatory. It leaves no room for discretionary bond hearings. It applies regardless of how long the alien has remained unlawfully in the country.

Physical presence does not confer the legal status or constitutional entitlements that accompany lawful admission, much less citizenship.

This ruling rejects the long-standing practice of treating interior illegal aliens as governed by the bond statute. As the Fifth Circuit panel made clear, that statute applies after lawful admission. It does not override Congress’ command for those who were never admitted at all.

No other federal appellate court has squarely held that mandatory detention applies not only to recent border crossers but also to long-term illegal aliens living in the interior who entered without inspection years — even decades — ago.

Long-delayed enforcement

Nothing in the Fifth Circuit’s decision turns on novel statutory interpretation. Congress enacted this framework in 1996 to eliminate incentives for evading inspection and remaining unlawfully in the United States.

What changed was not the law but the willingness to enforce it.

After the Board of Immigration Appeals acknowledged the plain meaning of the disputed section in Matter of Yajure Hurtado, DHS implemented a policy treating illegal entrants as Congress defined them: applicants for admission subject to mandatory detention.

The response was immediate and predictable. District courts across the country rushed to block the policy, issuing a wave of rulings restoring bond eligibility.

The Fifth Circuit is the first appellate court to say what should have been obvious all along: Courts do not get to rewrite immigration statutes because enforcement is politically uncomfortable.

RELATED: We escaped King George. Why do we bow to King Judge?

Photo by Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images

Photo by Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images

Asylum is not a loophole

One of the most persistent myths in immigration discourse claims that filing for asylum legalizes illegal entry. It does not.

Congress made illegal entry a federal misdemeanor. The statute contains no asylum exception. Illegal entry remains a crime even for those who later request asylum.

Asylum also does not create a “right to remain.” It is discretionary relief from removal.

Federal law allows an alien to apply for asylum after illegal entry. That provision does not cure inadmissibility, erase criminal violations, or entitle the applicant to release from custody.

When an alien crosses the border illegally — between ports of entry — the alien violates federal law and becomes inadmissible for lack of valid entry documents. That inadmissibility triggers expedited removal.

The law allows an alien to request asylum after unlawful entry, but it does not legalize the entry, erase inadmissibility, or prevent removal. In this posture, asylum is defensive. The alien raises it after DHS initiates removal proceedings, and the alien receives it, if at all, as discretionary relief — not as a right to remain.

Aliens who enter without valid documents remain inadmissible and subject to detention or removal.

Mandatory detention applies to many asylum seekers. Under the statute:

- Illegal entrants go into expedited removal unless they establish a credible fear.

- When an alien claims credible fear, the alien remains detained pending final adjudication.

- Release runs through limited DHS parole authority, not judicial bond hearings.

The Supreme Court confirmed this framework in Jennings v. Rodriguez (2018), holding that the statute mandates detention and does not allow courts to invent bond hearings where Congress declined to authorize them.

Law on the books vs. law in practice

The detention statute does not suffer from ambiguity. The conflict lies elsewhere.

Congress criminalized unlawful entry without exception. Congress also enacted the asylum provision through the Refugee Act of 1980, permitting any alien “physically present” in the United States or arriving at the border to apply for asylum regardless of manner of entry. That provision does not exempt such individuals from prosecution, detention, or removal. It does not repeal the detention mandate.

The Refugee Act incorporated aspects of the U.N. Refugee Convention and Protocol, including Article 31’s discouragement of “penalization” for unlawful entry in limited circumstances. Article 31 does not prohibit detention, prosecution, or removal. It confers no right to unlawful entry or release pending adjudication. Nothing in the treaty framework — or U.S. law — displaces Congress’ mandatory detention commands.

RELATED: Federalism cannot be a shield for sanctuary defiance

Photo by John Moore/Getty Images

Photo by John Moore/Getty Images

Over time, however, executive agencies — and sometimes courts — expanded a limited non-penalization principle into a broader immunity regime. Officials treated asylum eligibility as a basis to avoid detention, delay removal, and suspend enforcement mandates Congress never repealed.

That is not discretion. It is dereliction. It nullifies the statute Congress enacted.

Until Congress revisits asylum law or alters treaty commitments, that structural tension will invite exploitation — regardless of what the detention statute requires.

Why this ruling matters

By enforcing the law as written, the Fifth Circuit restored a foundational principle of sovereignty: Illegal entry does not generate superior legal rights.

The dissent warns that enforcing the statute could produce large-scale detention. That warning is not a legal argument. It is a policy objection rooted in disagreement with the statute Congress enacted.

This ruling binds only Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi — for now. Other circuits have signaled resistance. A split is coming. Supreme Court review seems likely.

When that moment arrives, the court will face a question it has avoided for years: Does immigration law mean what it says — or only what politics permits?

The Fifth Circuit has answered.

For the first time in decades, a federal court treated immigration law as law, not a suggestion.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0