They think 'Christian AI' will hasten Christ's second coming — and now they're building it

Artificial intelligence and Christianity were never meant to share a pew. One was built on the mystery of divine creation; the other on the arrogance of re-creation. One asks for faith; the other for feedback. Christ said, “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” Silicon Valley says, “We’re still in beta.” The two are about as compatible as the Garden of Eden and a Google campus.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

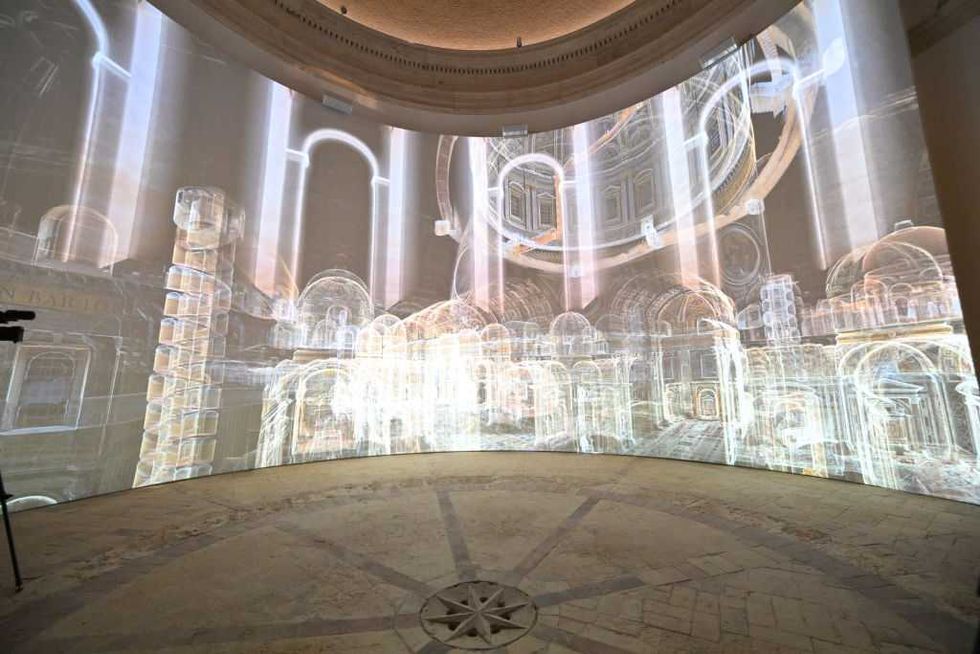

Without swift changes, the trajectory is clear: AI becomes man’s latest Tower of Babel — a cathedral without God, where the worshippers speak in code and measure divinity in data points. It promises omniscience without morality, communion without confession, salvation without sin. If AI seeks to simulate humanity rather than serve it, when imitation becomes indistinguishable from incarnation, the heresy is complete.

We're reluctant to realize until it's too late that we built a golden calf with customer support.

There’s something absurd about watching tech CEOs quote Scripture as they roll out neural networks. Patrick Gelsinger’s “Christian AI” through his company Gloo is a fine example — an attempt to digitize devotion, automate the altar, and outsource the soul. He speaks of hastening “the coming of Christ’s return,” as if the Second Coming might now depend on cloud storage and quarterly funding rounds. The Reformation had Luther and the printing press; Silicon Valley has sermon slides and subscription tiers.

To say AI and Christianity neatly align is to confuse omniscience with omnipotence, a mix-up Gelsinger seems to find profitable.

Christianity begins with the admission of imperfection — that man is fallen and must be redeemed. The nascent church of AI begins with the belief that perfection is achievable, just one dataset and funding round away. One kneels before mystery; the other dissects it. To the Christian, knowledge without humility is literally the oldest sin in the book. To the eschaton-immanentizing technologist, it’s the business model.

What sermon can stop the theological train wreck? AI is coming for everything — art, law, love, and, inevitably, faith. It will write psalms, confess sins, and deliver homilies with the warmth of a toaster. It will perform digital miracles that leave priests wondering if they should have learned Python. Already, chatbots soothe the lonely and counsel the broken. Tomorrow they’ll offer absolution, complete with a “forgive me” button and instant feedback on spiritual progress. The modern confessional booth will be equipped with terms of service.

The danger, I suggest, isn’t that AI will destroy religion but, in our convenience-hungry culture, out-market it.

RELATED: Google’s AI called Robby Starbuck a predator. Now he’s suing.

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

Hope with a progress bar, delivered quietly, efficiently, and with better UX. People won’t pray but prompt. They won’t seek God’s voice; they’ll fine-tune a model until it tells them exactly what they wish He’d say. That’s the tragedy of this new gospel: It offers comfort without conviction, certainty without sacrifice. It gives you grace without God.

Still, mere mockery of Gelsinger’s “Christian AI” misses a deeper truth. The age of AI isn’t waiting for our theological approval. A machine doesn’t care whether you call it sacred or satanic. Regardless, it can learn your hymns, mirror your morality, and sell you an app that scores your sanctity. The church can ignore it, or it can prepare for the reckoning. Because whether you like it or not, the algorithm is coming for Sunday service.

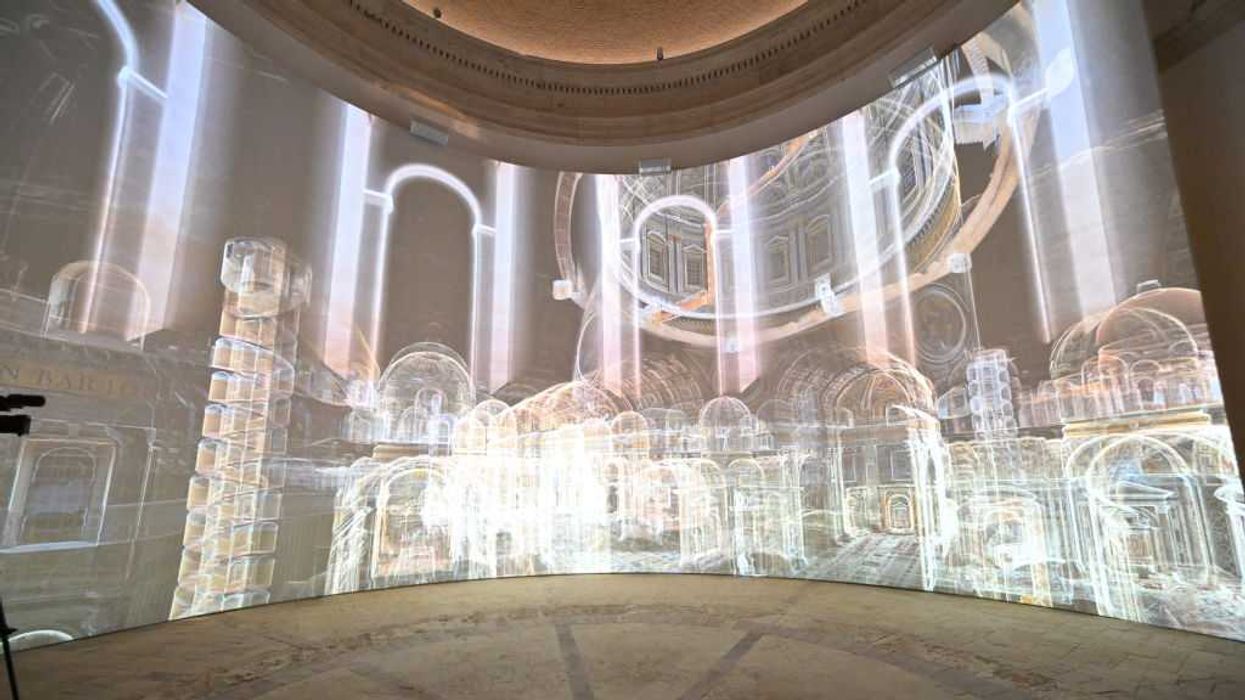

So what would a respectable Christian AI look like? Not Gloo’s chipper chatbot that mistakes engagement metrics for evangelism. Not another “faith tech” product designed to “optimize ministry engagement” or “gamify discipleship.” A respectable Christian AI would reflect restraint, not reach for reverence. It would refuse to pretend it knows God’s will, and it would never charge a fee to interpret it. It would encourage silence over speech and contemplation over computation.

In short, it would imitate the virtues of the church, not the vanity of its donors.

Imagine an AI that didn’t flatter human desire but challenged it. An AI that told uncomfortable truths instead of personalized platitudes. One that said, “No, you’re not special,” and meant it lovingly. It would not track your prayers like Fitbits track your steps; it would remind you that prayer is more intimate than an input ever can be. It wouldn’t replace your priest or pastor. It would remind you to see him in person.

But will we build that AI? Silence and modesty don’t tend to attract venture capital. Silicon Valley prefers small-g gods it can measure and monetize. The market has little use for mystery. And so we march, like digital Israelites, toward a promised land of perfect prediction, reluctant to realize until it's too late that we built a golden calf with customer support.

If Christianity survives the algorithmic age, it won’t be because it out-coded Google. It will be because it remembered what no machine can: that conscience cannot be coded, wonder cannot be wired, and the divine resists human design. Faith was never meant to be efficient, and salvation is not a software update.

AI will teach us many things about ourselves: our hunger for control, dread of solitude, and addiction to ease. But perhaps, in its cold imitation of creation, it will also remind us why we need the real thing. When the screen insists, “I am always here,” the believer should reply, “So is God, and you’re not Him.”

In the end, maybe that’s the only way to keep faith alive. Not by competing with the machine, but by refusing to become one.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0