Tokyo Inferno: Operation Meetinghouse, The Deadliest Air Raid In History, Part 1

On November 15, 1941, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall gave a secret briefing to a small group of reporters to discuss the rising tensions between Washington D.C. and Tokyo. He was asked how the U.S. might prosecute a war against Japan if it should come to that. Marshall went off the record, and stated we would be merciless. American aircraft would be “dispatched to set the paper cities of Japan on fire. There won’t be any hesitation about bombing civilians — it will be all out.”

Just three weeks later, Pearl Harbor was attacked and the U.S. found itself at war with the Japanese empire. With the exception of Col. Jimmy Doolittle’s celebrated, if mostly symbolic, April 1942 raid the enemy’s homeland remained safely out of range.

As the Americans began to press ever closer to Japan in a series of island hopping operations through the Central Pacific, however, it became clear that once the Marianas were captured this situation would change.

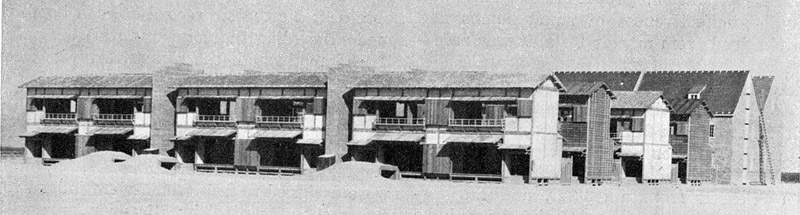

In 1943, out in the Utah desert on the Dugway Proving Ground, the Army Air Force constructed a 24-building replica of a Japanese city. There they ran a series of tests to determine how best to bomb a metropolitan area with wooden structures containing paper walls. Inside the imitation homes were pieces of imported Japanese furniture, tatami mats, and even clothes hung in the closets for authenticity. With forensic dispassion, they dropped various ordinances on the miniature city dubbed “Little Tokyo” to determine which was most effective.

View of the German and Japanese Village at Dugway Proving Grounds, Utah, 1943. US ARMY, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The weapon chosen was the new M69 napalm bomb. It was a simple design. Weighing under seven pounds, it didn’t look like a typical bomb. Instead it was a hexagonal pipe just three inches in diameter and only 20 inches long and packed with cheesecloth bags loaded with napalm. The bomb trailed a three-foot streamer to slow its descent so it wouldn’t crash through a structure to the basement before igniting. Once the M69 pipe landed it lay inert for several seconds before shooting out the cheesecloth bags with a bang. Unimpeded, the bags could fly as far as a football field’s distance in any direction. If one should hit something in its path, like a wall, a ceiling, a car, a person even, the bag would burst like a water balloon, splattering a glob of flaming gel up to 50 feet, starting hundreds of intense mini fires. And they kept burning until the small fires eventually coalesced into an inferno, ravenously feasting on the ready fuel supply of Japanese wood and paper.

The destructive implications were disquieting. Potential civilian casualties would be on an order of magnitude never before seen. This at a time when firebombing Axis cities, like the RAF raid on Hamburg in July 1943 that killed 45,000 civilians, had already come into its own. By this stage in the war, however, with casualties mounting and Japan showing no inkling towards surrender, American hatred for the Japanese was so intense that personal scruples hardly entered into the calculation.

Meanwhile, the engineers at Boeing Aircraft had created an awesome delivery system to bring the war to Japan: The B-29 long range bomber. With a fuselage length of 99 feet and wingspan of 140 feet, the aptly named “Superfortress” was the largest, most technologically advanced mass-produced weapon of the Second World War. Driven by four 2,200 horsepower Wright R-3350 engines mounted on wing nacelles spinning four 16-foot 7-inch four-bladed propellers, and protected by remote-control gun turrets, the 60-ton wonder plane sped through the air at up to 350 mph at 30,000 feet. Pressurized compartments liberated the crews from the bulky flight suits and oxygen masks at altitude that were a necessity for the aviators on the B-29’s less advanced stablemates, the USAAF B-17 and B-24 and RAF Lancaster. Despite its size and weight, the Superfortress could hit targets 1,600 miles away with a 12,000 pound payload at altitude. The B-29 was to the other bombers in the Allied arsenal what the Cadillac DeVille was to the Model-T.

Bell-Marietta Georgia, B-29 Assembly Line – 1944. Serial numbers on the planes suggest these are Wichita-built Boeing B-29-5-BWs. U.S. Army Air Forces, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

But having spent an unprecedented $3 billion in 1940s dollars designing, constructing ,and deploying the new leviathan bomber, U.S. planners feared they may have created the costliest flop in military history.

For all its promise and technological wonder, however, the B-29 was proving to be a disappointment.

Flying first off of bases on mainland China and then, once captured, the Marianas, the B-29, would climb to its prescribed bombing altitude of 30,000 feet. Once there, the aircraft encountered the heretofore unheard of jet stream — a current of air that raced over Japan like an angry “kaze”, or wind, at 250 mph. When flying perpendicular to it, the bombers skidded wildly off course. If flying directly into it, real ground speed was reduced to a crawl, making the bombers easy targets for anti-aircraft. And if the kaze was in their six, the bombers raced headlong over their targets at speeds in excess of 450mph which was far too fast for accurate bombing. The results were negligible, and each time a B-29 was shot down, $600,000 worth of aircraft (in a time when a typical new house cost $3,100) and anywhere from ten to fourteen highly trained crewmen were lost. And, though greatly diminished by mid-1944, Japanese fighters still rose up to challenge the intruders over their cities.

In its first raid against Japan on June 15, 1944, for example, 60 China-based B-29s flying at 30,000 feet attempted to bomb a steel mill in Kyushu. Seven bombers were lost, while only one bomb hit the target. Something had to be done to salvage the B-29.

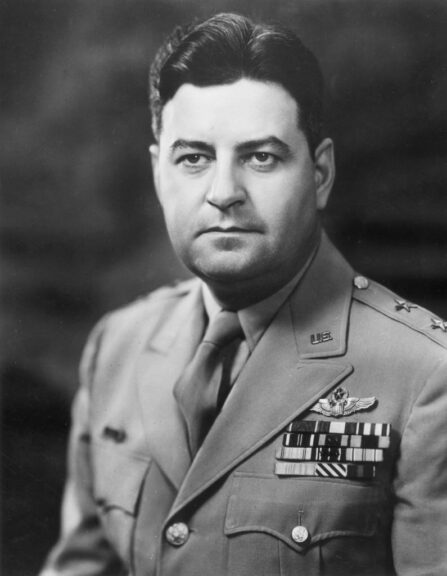

So the overall USAAF commander, Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, reached over to the European Theater and summoned his most aggressive airman, Gen. Curtis LeMay, to take over the Pacific strategic bombing campaign from Gen. H.S. Hansell, who remained a stubborn disciple of high altitude precision bombing with high explosives. Arnold’s orders to LeMay were direct: get results or be fired too.

circa 1955: Studio portrait of United States Air Force Major General Curtis Emerson Le May wearing a military uniform, with medals over his left breast pocket. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The cigar-chomping LeMay was known as a no-nonsense bomber ace who’d flown his share of combat missions over Germany, often piloting the lead plane into the flak and Luftwaffe-filled skies. He brought that same gritty determination to the Pacific.

At first, LeMay stayed true to daylight precision bombing dicta. But dropping high explosives on Tokyo from six miles up was proving ineffective. So on February 28, 1945, LeMay did something unorthodox. He sent his bombers high over Tokyo again, but this time they carried 450 tons of incendiaries. The results were encouraging; one square mile of Tokyo was burned out and 28,000 buildings destroyed or damaged. The general wondered what a mass raid coming in low could do.

LeMay summoned his wing commanders to his Quonset hut on Guam to inform them he’d made a stunning, and some thought insane, decision. He would bring the B-29s down under the jet stream to an altitude of between 5,000 and 8,000 feet. To impede anti-aircraft they would go in under the cover of night and the bombers would be loaded to the gills with M69 napalm bombs. And as if this wasn’t radical enough, LeMay informed his flabbergasted crews “I’m going to send you in at 5,000 feet without any guns, gunners or ammunition.” Though stripping away the heavy .50 caliber machine guns and extra crewmen would enable each bomber to haul an additional 2,700 pounds of ordinance, each aircraft would now be defenseless.

LeMay’s fliers were horrified. In fact, they saw the mission briefing as tantamount to a madman reading out their collective death sentences. There was safety in altitude. Said one aviator, “A sort of cold fear gripped the crew. Many frankly did not expect to return from a raid over that city at an altitude of less than 10,000 feet.” This wasn’t hyperbole. LeMay’s own flak experts feared that as many as seven out of ten bombers could be lost.

But the calculating airman thought he’d spotted a hole in Japan’s air defenses between low-level small caliber and high-altitude larger caliber anti-aircraft fire in that five to ten thousand corridor. He also knew there were only two dedicated night fighter squadrons on Tokyo’s Honshu island.

Dangers aside, there was a moral aspect to the new mission code-named “Operation Meetinghouse.” The specific target selected was a three-by-four-mile area that housed an estimated 750,000 people, many of them working as home-based shop laborers for the local war factories, which the planners figured made the zone a legitimate military target. Still, LeMay had no delusions as to what he was asking of his young fliers, and he was coldly candid in his briefing. “No matter how you slice it, you’re going to kill an awful lot of civilians. Thousands and thousands. But if you don’t destroy Japanese industry we’ll have to invade Japan.” Every man knew the horrific casualties such a final Götterdämmerung on the home islands implied.

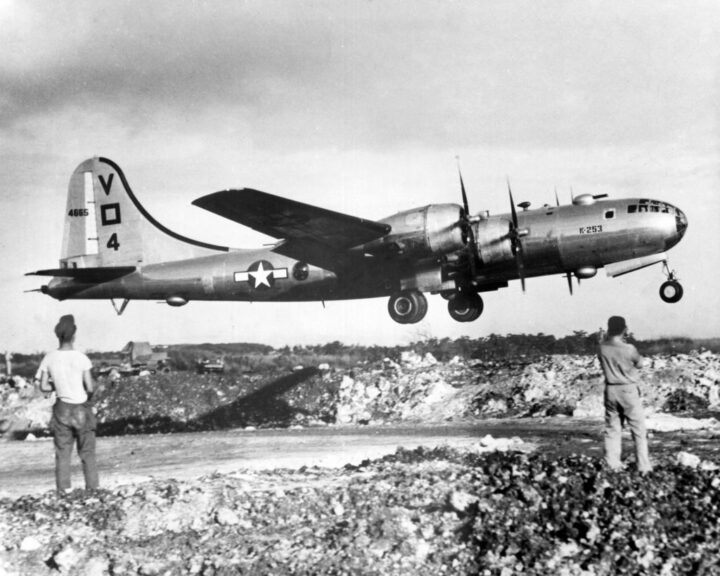

At 5:35 p.m. on Friday, March 9, 1945, the first of 324 B-29s, carrying a combined payload of three and a third million pounds of napalm, roared down the runways on three Marianas islands; first Guam, which was farthest from Japan, then forty minutes later lifting off from Saipan and Tinian. Once in the air, the bombers headed for Japan in three parallel streams stretching 400 miles across the darkening Pacific sky.

Two U.S. soldiers watching the takeoff of a B-29 bomber from the air base at Saipan, destination Tokyo. Saipan, 23rd November 1944 (Photo by Mondadori via Getty Images)

LeMay, being LeMay, had wanted to lead the mission himself as he was going all in, betting hundreds of expensive bombers, and the young lives of their crews, on an untested theory. But his knowledge of the atomic bomb made his capture too high a security risk, so he was compelled to stay behind on Guam and pace his control room while furiously chomping his cigar. For the first time in the war, Curtis LeMay could not sleep. “I’m sweating this one out,” he confessed. “A lot could go wrong.”

501st Bombardment Group B-29 takeoff Northwest Field Guam. U.S. Army Air Forces, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

1,500 miles farther north, Tokyo’s teeming inhabitants had no clue as to the holocaust heading their way. All they knew from Radio Tokyo was that tomorrow, March 10, was Army Day. There would be a big parade through the streets. After reading the latest news, Radio Tokyo offered final words of encouragement to stay strong in the face of mounting adversity. “It is always darkest before dawn,” said the announcer. Then he wished them a good night and signed off.

Shortly after the radio went silent, six-year-old Suzuki Kensuke heard the blare of air-raid sirens erupting across the city, mingling with the ominous hum of thousands of approaching radial engines echoing through the night sky. “They sounded like an advanced notice telling us death was on the way,” he recalled. Death was, in fact, already overhead.

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages of The Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge, and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0