Clemency and Capital Crimes: Biden’s Travesty of Injustice

Two days before Christmas 2024, President Joe Biden commuted the sentences of 37 of 40 federal death row inmates. Five of these had murdered children; several had murdered multiple people and on separate occasions.

Among those whose death sentence was commuted was Thomas Sanders, who on Sept. 8, 2010, in Louisiana kidnapped a 12-year-old girl, shot her, and slit her throat. This atrocity occurred only days after the girl was held captive and forced to witness Sanders’ murder her own mother.

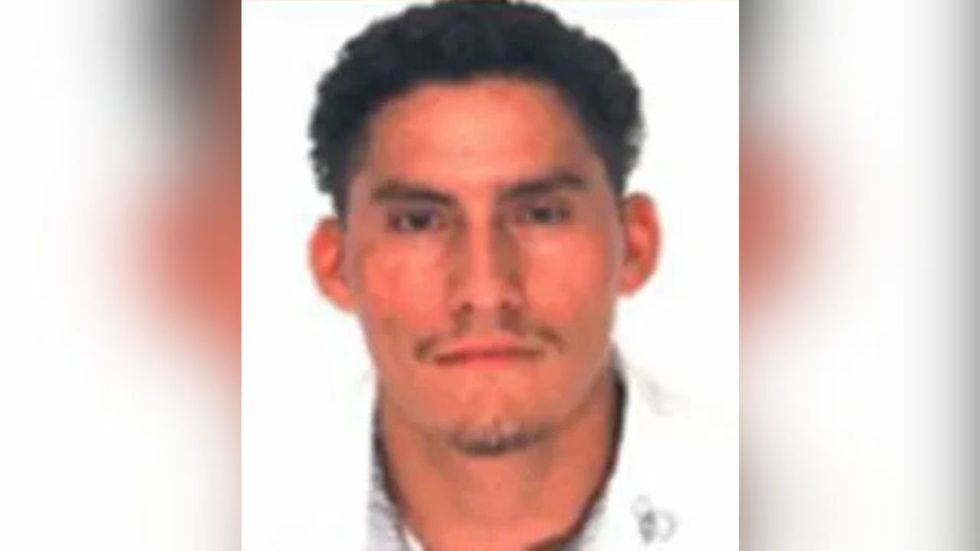

Another whose death sentence was commuted was Jorge Avila-Torrez, who in 2005 in north Chicago sexually assaulted and stabbed to death two girls, an eight and nine-year-old. Four years later, Avila-Torrez assaulted a 20-year-old woman and naval officer in Northern Virginia, strangling her to death in her own barracks.

Yet another recipient of Biden’s Christmas package was Kaboni Savage, a Philadelphia drug kingpin who had masterminded or participated in 12 murders, including the 2004 firebombing of a federal informant’s home in which a mother, a son, and four relatives were killed.

It doesn’t stop there. The list goes on.

On Dec. 12, Biden commuted the sentences of roughly 1,500 people, the “largest single-day grant of clemency” in U.S. history among presidents. His stated aim was to prevent President-elect Donald Trump from “carrying out the execution sentences that would not be handed down under current policy and practice.”

Given Biden’s commitment, even in a lame-duck context, to undermine the incoming administration’s policy prescriptions, the clemency issued to virtually all federal death-row inmates raises important questions for American culture: Are these acts of clemency really justice?

Consider Biden’s rationale for his actions: “ensuring a fair and effective justice system,” the outlandish hypocrisy of which begs multiple questions. And note Biden’s explanation: “guided by my conscience my experience as a public defender, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, vice president, and now president, I am more convinced than ever that we must stop the use of the death penalty at the federal level. In good conscience, I cannot stand back and . . . resume executions that I halted.”

This, of course, is the same president who on Dec. 1 issued a blanket pardon for his son who was charged in June with three federal gun felonies and who pleaded guilty in September to tax fraud in the amount of $1.4 million due to foreign business dealings. The father has claimed that the son was unfairly targeted?by the Department of Justice.

Such 11th-hour madness is only the latest evidence of an issue that simply will not go away, despite our cultural unwillingness to confront it. It is the issue of justice, and it will visit us tomorrow again, in increasingly forceful ways.

In a past generation, it concerned what to do with people like Karla Faye Tucker, Timothy McVeigh, and the “Unabomber.” Closer to our day, it concerned our response to outrages such as the Boston Marathon bombings and the Washington, D.C., mansion murders.

Today, it confronts us, among other ways, in the form of mass murders in our schools. Recall, for example, that in 2018, a Florida jury recommended a life sentence without parole instead of the death penalty for the man who murdered 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. It also confronts us in the cold-blooded killing of organizational CEOs, something that is only days removed from us.

Tomorrow, rest assured, we will be confronted with the unthinkable in even more frightening dimensions.

The dogged fact remains that people do evil things to their fellow human beings, and this is because of our fallen nature. Of course, we place our faith in psycho-social studies, brain research, pharmacology, and preventive biogenetics in the hopes of altering that stubborn reality.

Alas, in the end, these preemptive strategies will only make us less morally responsible, and thus less human. The question, at bottom, is whether a civilized culture will tolerate those who murder in cold blood and whether we are willing to clear our throats and make moral judgments.

One would hope that the increasingly barbaric face of crime in our nation as mirrored in murder rates might ensure that debates over capital punishment would intensify. This, strangely, has not been the case.

According to The Marshall Project, more mass shootings (i.e., four or more victims) have occurred in the last five years than in any other five-year period since 1966. This should give us pause. We are surely justified in asking, even when it is not socially or politically expedient in our day, what murderers deserve. No civilized nation or people-group takes the matter of murder for granted; no civilized society is casual about its response to the need for protecting the wider common good.

What is striking, in fact, is the relative absence of discussion and debate over the death penalty. As with most social-political controversies, the debate over capital punishment—when that debate occurs, that is—proceeds quite frequently along two misguided trajectories: either along emotional and mental health lines or under the guise of racial imbalance.

Missing in most discussions is any sense of the grounding of justice–philosophical and/or theological. Properly construed, justice must verify society’s commitment to guarding the common social good.

The matter of murder and the question of capital punishment raise unavoidable foundational issues for “civil society.” Unhappily, the moral foundations of law are dying in the West, and this, of course, did not begin yesterday. The shift of America’s public philosophy of choice has been in progress for generations, whereby a militantly secularized understanding of law—and hence, of public morality—proceeds unabated. To inject the moral viewpoint—quite vividly on display in the context of capital punishment—into contemporary social- and public-policy debates is an anathema. It is decried as “hate-filled,” “bigoted,” and “intolerant.”

Justice, however, depends on something beyond itself. To render what is due is to require a foundation and understanding of moral truth, which is not fluid.

The chief victim in all of this late-term madness is justice. Contrary to contemporary practice in most jurisdictions and presidential bluster, punishment for a crime and restitution for the victim are interrelated concepts. In the case of premeditated murder, compensation is not available as an alternative.

As virtually all of human history attests, including the Western cultural tradition until very recently, premeditated murder is the one crime that carries a mandatory death sentence. To suggest or argue that the ultimate human crime should not be met with the ultimate punishment being meted out by civil authorities, at least in a relatively free society, is not some “higher” ethic as many might contend. Rather, it is a moral travesty inasmuch as it fails to comprehend the nature of human dignityand stubbornly contradicts universally revealed canons of moral truth.

Such indignity guarantees a collapse of civil society as we know it.

The post Clemency and Capital Crimes: Biden’s Travesty of Injustice appeared first on The Daily Signal.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0