Cooking is easy; it's our modern anxiety that makes it hard

Millions of modern Westerners are chained up in self-imposed terrors that prevent them from living in the real world. We’re terrified of “expired” food. We consult the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's website while we peer at our digital meat thermometers to make sure we hit the government-approved specific temperature that reassures us that we won’t kill our families.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

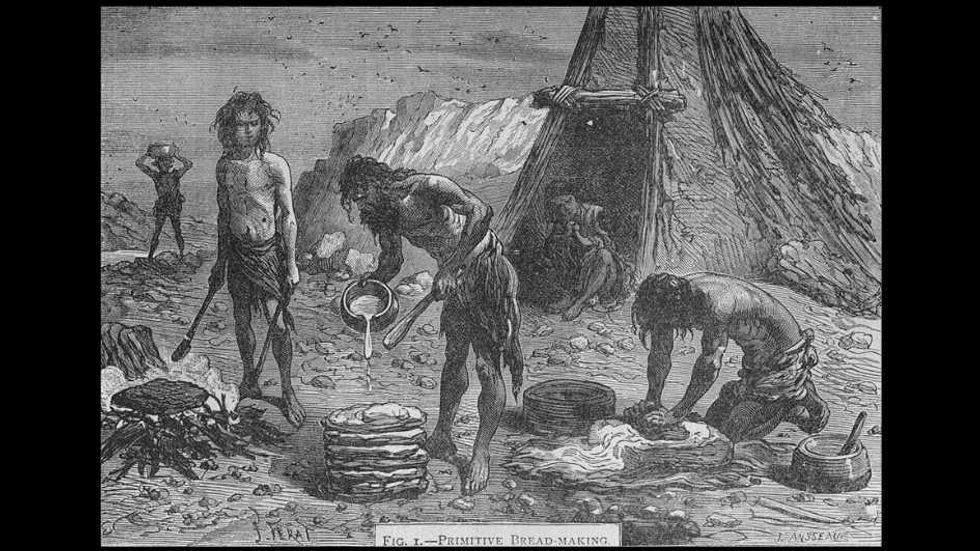

You can just cook things. Do you know that? Really. You can do the same things, with the same basic tools, that humans have been doing for countless tens of thousands of years before programmable stoves, digital scales, and tenth-of-a-degree meat thermometers came along. The only thing stopping you is unnecessary fear.

There is no reason to be reliant on complicated devices and prissy little scales in order to make bread. How do you think Laura Ingalls managed it?

It’s not just cooking that’s fallen prey to modern hysteria either. Alleged adults in the 2020s are skittish about checking the oil in their car or topping up the antifreeze (if they even think it’s “safe” to do without professional supervision).

Food for thought

But I can only focus on one thing in this piece, and that’s going to be food. Between the time I was a kid learning to cook in the '80s and today, adult Americans have retreated into a mental padded cell where they quake with overblown fears about food technique and food safety.

I come from the Before Times, a land where children walked a mile each way to school, a land where kids could ride their bikes anywhere in town as long as they were home by dark. Now we have a new traffic jam at 3 p.m. around public schools. It’s not normal. It’s also not sane, necessary, or proportionate. Today only one in 10 children walk to school. Read that again. If that sounds normal, you’re the person I’m writing for.

I was taught to use a stove for simple meals by the time I was 8. Today? Fourteen-year-olds on average have never even made a box of macaroni and cheese on the stove top. A few years later, they become 25-year-olds who complain about the cost of eating because they think — yes, really — that DoorDash is the normal way to get supper.

I'm with soup-id

I knew something was happening to adult minds back in 1991 in the staff room of Perkins Family Restaurant in Camillus, New York. It was 2 p.m., and I was struggling to stay awake for an all-hands meeting on food safety (I worked the overnight shift).

District manager Phil was telling us about the dangers of poultry and salmonella. You have to know there was no raw poultry in the kitchen of this restaurant ever. Every chicken product we served had been pre-cooked, which means that any salmonella had already been killed. We merely reheated plastic-bagged refrigerated food from a factory.

Phil opened a bag of fully cooked chicken and dumpling soup and poured it into the steam table. Whipping out a thermometer, he stuck it into the next pot, which already had the same soup brought to serving temperature.

“This pot is not hot enough, and if we don’t keep it up to temperature, we risk giving our guests salmonella poisoning,” he said.

I bit my hand to stop myself from responding.

In case you don’t know why this is wrong: Once poultry has been fully cooked, all salmonella gets killed. It does not “regenerate” if the temperature falls. Sure, other microbes might get a foothold, but this guy really did believe that letting chicken cool off a few degrees would magically re-salmonellize it. I wonder if he believed the old tale about how raw meat spontaneously generates flies.

RELATED: How I stopped hating guns — and embraced self-reliance

Angus Mordant/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Angus Mordant/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The d'oy of cooking

As a longtime home cook, I’ve watched cookery become hystericized over the past four decades. As fewer parents cooked themselves, and as even fewer of them taught their children, I watched recipes get dumbed down. What would have taken a paragraph to explain to a person in 1985 now required 15 numbered steps: “Pour water into clear container. Bending down, use your eye to see if it hits the line that says ‘one cup.’ Then carefully pick up the cup, and tilt it so that the water falls out into the bowl. This is called ‘pouring.’”

I only slightly exaggerate. About 15 years ago, I looked up a recipe for chicken paprikash and made the mistake of reading the comments. This is a pretty accurate reconstruction:

“I made this recipe exactly as the author described, but she never told me that there were BONES in the chicken. I was appalled! I actually served my family chicken with bones inside it, and I was so embarrassed. My kids wouldn’t eat it. You should WARN PEOPLE.”

No, I don’t think this commenter was a troll. I’ve seen enough in real life to know there are millions of Americans walking around so disconnected from basic household tasks that they literally do not know that meat always comes with bones and that bones are normal.

Getting medieval

Last week, I got inspired to start baking again. That inspiration came from a YouTube channel I recommend called "Medieval Way." The British guy behind it takes you through the simple, manual, methods of raising bread, stewing meat, and preserving foods that people did from muscle memory and common sense. And wouldn’t you know, their foodways (which were the foodways for all of us for thousands of years before the late 19th century) produce more nutritious meals than most of us eat today.

It’s a myth, and a damned scurrilous one, that a noticeable number of people died all the time in “the old days” from food poisoning because they didn’t have refrigerators or meat thermometers or the CDC. Pardon my frankness, but all humans who lived before us weren’t stupid.

I decided I was going to resume sourdough baking from natural leaven, no commercial yeast. But I also decided I wasn’t going to buy any special equipment like scales or filtered water or any of that. And I wasn’t going to measure anything.

I want to master my craft with my hands and heart and eyes. There is no reason to be reliant on complicated devices and prissy little scales in order to make bread. How do you think Laura Ingalls managed it? She learned how dough felt in the hand and gauged proper hydration and texture through feel and experience. I can too. So can you.

Maybe my project will inspire you. Here’s what I did. Don’t expect precise measurements or special tips: Get in there with your hands and learn it yourself.

For the starter

- Stoneground organic whole rye flour. I’m not a hippie leftist; it’s just true that stone-ground flours without pesticides are nutritionally superior and give better results for this. Rye works faster than white flour.

- Water. I’m lucky enough to live on clean well water without chlorine. If you have city water, pour out a jug and set it on the counter to let the chlorine evaporate. That chemical will inhibit the bacteria and yeast you want to grow.

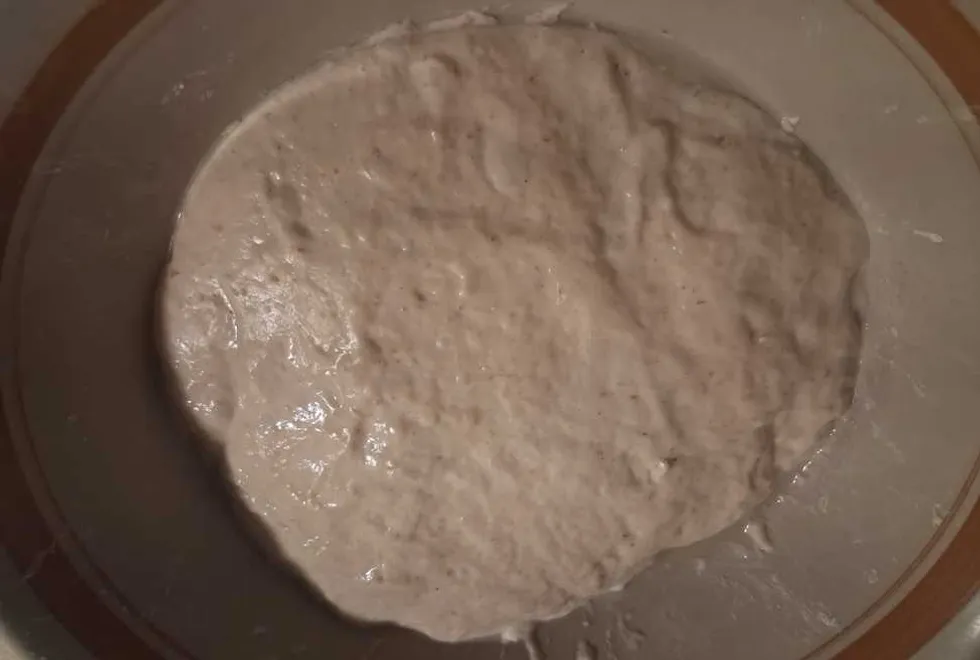

I put some flour in a bowl. Then I put some water in. Then I stirred it. Then I set it on the counter under a towel. Every day, I dumped half out and added back water and flour to give the nascent yeast new starch to grow on.

After a week, I wasn’t seeing much. I was on the verge of throwing it out and starting again when I lifted the towel and saw this:

Josh Slocum

Josh Slocum

That’s a thriving, frothing stew of natural yeast and accompanying bacteria that will leaven your loaf and give you a flavor you can’t get from commercial bread. It costs literally pennies and time.

For the bread

I put some all-purpose flour (again, organic, so no chemical traces to interfere) in a bowl. I added some lukewarm water. Then I dumped some of the starter in. How much? I don’t know. Maybe half a cup?

I mixed it all together and kneaded it just a few times until everything was incorporated. Tip: You don’t have to knead your dough at all if you’re willing to be patient. If you set a sourdough loaf to ferment in a room of about 60 degrees with a loose cover and wait 24 hours, the bacteria and yeast will do everything for you, and it's better than hand kneading.

Here’s the loaf 12 hours later:

Josh Slocum

Josh Slocum

It’s only risen about 20% to 30% in size so far, but that’s because sourdough is slower than commercial yeast, and my house is on the cool side. I’m going to put it in the oven with just the oven light on to speed it up.

How long will it take to double in size? I don’t know. It might do so by 24 hours, or it might take 36 hours. The longer the fermentation, the more digestible the bread, the better the texture, and the better the flavor. Sooner or later, it will fully rise, and I’ll pop it in a preheated, covered dutch oven at 500 degrees, and I’ll get a beautiful loaf with that crisp, glass-shattering crust.

My hope is that you’ll find something — bread, cakes, roast meats, whatever you like — and just cook it. Put down your cookbook. Turn off the phone. Stop looking for a “foolproof” recipe for bolognese sauce. Stop watching step-by-step videos.

Learn it in your hands and in your mind. Even most “mistakes” in cooking aren’t fatal to the meal. We don’t have to be slaves to expert directions. None of this is arcane knowledge beyond mere 21st-century mortals. Peasants who lived quite literally on one penny a day turned out two or three meals a day for their families without any of the gee-gaws and expert hand-holding that we moderns have become dependent upon.

Just go cook things!

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0