Homeowners' associations weren’t supposed to replace civilization

Homeowners’ associations exploded across America beginning in the 1960s. No one describes HOAs as “popular,” and the horror stories of petty rules and bureaucratic neighbors are legion. Yet more Americans fight for the privilege of buying into them every year. The reason is simple: The HOA is the last legal mechanism Americans have to artificially recreate something the country once produced organically — a high-trust society.

Live Your Best Retirement

Fun • Funds • Fitness • Freedom

People want neighborhoods where streets feel safe, houses stay maintained, and neighbors behave predictably. We call these places “high trust” because people do not expect those around them to violate basic standards. Doors remain unlocked, kids play outside, and property values rise. Americans once assumed this was the natural condition of ordinary life. It never was.

Everyone complains about HOAs, but they remain the only defense against the chaos modern culture produces.

High-trust societies are not accidental. They emerge only under specific cultural conditions. Trust forms when people can understand and predict the behavior of those around them. That requires a shared standard — how to act, how to maintain property, how to handle conflict. When those standards come from a common way of life, enforcement becomes minimal. People feel free not because they reject limits, but because the limits match their instincts and expectations.

Every social order requires maintenance, but the amount varies. When most residents share the same assumptions, small gestures keep the peace. A disapproving look from Mrs. Smith over an unkempt lawn prompts action. A loud party until 1 a.m. results in lost invitations until the offender corrects the behavior. Police rarely if ever enter the picture. The community polices itself through mutual judgment.

Several preconditions make this coordination possible. Residents must share standards so violations appear obvious. They must feel comfortable addressing those violations without fear of disproportionate or hostile reactions. And they must value the esteem of their neighbors enough to respond to correction. When those conditions collapse, norms collapse with them. As New York learned during the era of broken windows, one act of disorder invites the next.

American culture and government spent the last 60 years destroying those preconditions.

Academics and media stigmatized culturally cohesive neighborhoods, and government policies made them nearly impossible to maintain. Accusations of racism, sexism, or homophobia discourage the subtle social pressure that once corrected behavior. The informal network of mothers supervising neighborhood kids vanished as more women entered the corporate workforce. And as Robert Putnam documented, social trust deteriorates as diversity increases. Residents retreat into isolation, not engagement.

The HOA attempts to reconstruct a high-trust environment under conditions that no longer support it. Ownership, maintenance, and conduct move from cultural consensus to legal contract. Residents with widely different expectations sign binding agreements dictating noise levels, lawn care, parking, paint colors, and countless other micro-regulations. A formal board replaces Mrs. Smith’s frown. Fines replace gentle rebukes. Gates and walls replace the watchful eye of neighborhood moms.

What once came from community now comes from bureaucracy.

With home prices surging, families dedicate larger portions of their wealth to their houses. Few want to gamble on declining property values because their neighborhood slips into disorder. Everyone complains about HOAs, but they remain the only defense against the chaos modern culture produces. People enter hostile, artificial arrangements where neighbors behave like informants rather than partners — because the alternative threatens their largest investment.

RELATED: Do you want Caesar? Because this is how you get Caesar

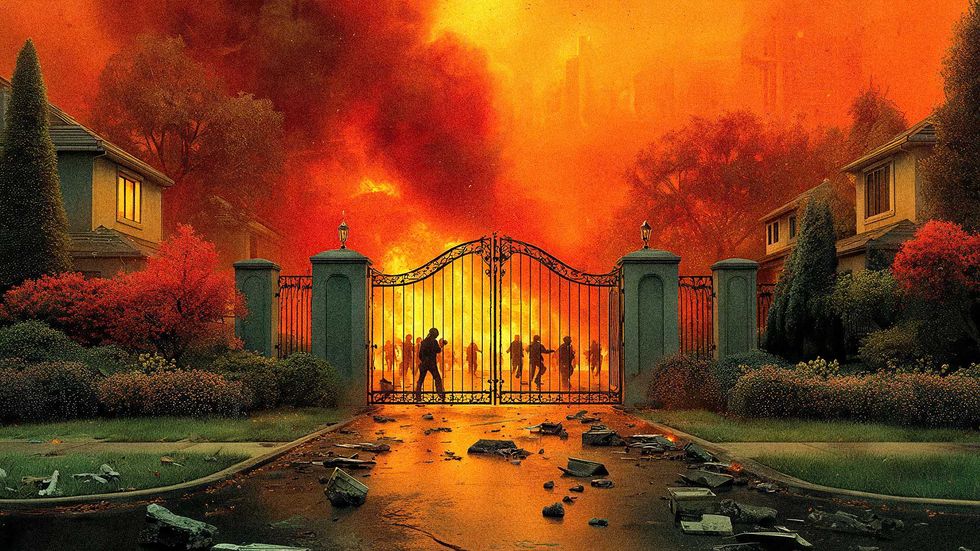

Blaze Media Illustration

Blaze Media Illustration

This analysis is not about suburban frustration. The HOA reveals a far broader truth: Modern America replaced a high-trust society with a trustless system enforced by administrative power.

As cultural diversity rises, the ability of a population to form democratic consensus declines. Without shared standards, people cannot coordinate behavior through social pressure. To replicate the order once produced organically by culture, society must formalize more and more interactions under the judgment of third parties — courts, bureaucracies, and regulatory bodies. The state becomes the referee for disputes communities once handled themselves.

Litigiousness rises, contracts proliferate, and coercion replaces custom. The virtue of the people declines as they lose the skills required to maintain trust with their neighbors. Instead of resolving conflict directly, they appeal to ever-expanding authorities. No one learns how to build trust; they only learn how to report violations.

The HOA problem is not really about homeowners or housing costs. It is a window into how America reorganized itself. A nation once shaped by shared norms and informal enforcement now relies on legalistic frameworks to manage daily life. Americans sense the artificiality, but they see no alternative. They know something fundamental has changed. They know the culture that sustained high-trust communities no longer exists.

The HOA simply makes the loss unavoidable.

Originally Published at Daily Wire, Daily Signal, or The Blaze

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0